The Venture Dairy Story

After exiting a $500 million by sales firm he helped build, Trevor Tomkins visited dairy farms across 5 continents, found the same broken system everywhere and built an investment firm to help fix it.

“I had to go to our shareholders and ask for a loan of $500,000 so I could meet payroll,” recalls Trevor Tomkins, describing his second week as president of Milk Specialties (now known as Actus Nutrition) in 1996.

The animal nutrition company was hemorrhaging $3 million annually when Trevor, then 47, took the helm after a management crisis.

The company's then-CEO had instructed Trevor to lie to the board about a product's FDA approval status.

He refused.

“It was totally unethical. I got advice from a Chicago law firm. And they suggested that I write to the shareholders and tell them what was going on. So I wrote to the shareholders and said, you know, I'm basically blowing the whistle,” Trevor recounts.

This act of integrity, which could have ended his career, instead became its defining turning point.

The risk paid off. Within days, the CEO was fired, the major debt holder converted their stake to equity, and Trevor was asked if he could take over as president.

He agreed.

He immediately refocused the company on fundamentals:

“Know your customers well, and then know and understand the products the customer wants.”

From that ethical stand, Trevor would transform a failing $53 million company into a nearly $500 million (by revenue) enterprise in just 15 years when he retired—and currently $1.5 billion+ dollars in revenue today—all while adhering to principles he learned from a small dairy farmer in England: his grandfather.

Table of Contents

Early Life

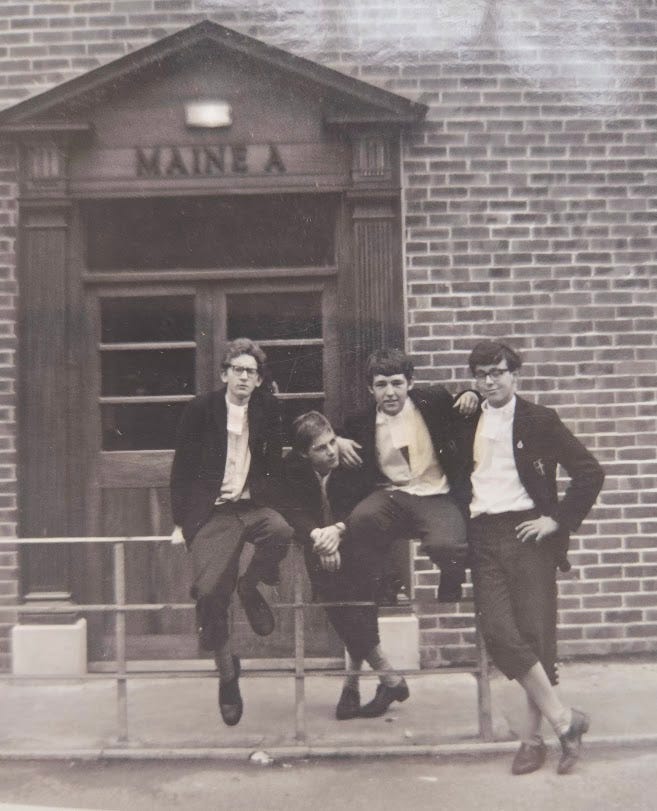

Born in 1949 in Hemel Hempstead, a small town north of London, Trevor's journey began with tragedy.

His father, William Gordon Tomkins an airline pilot for British European Airways (a predecessor to British Airways), was killed in an aircraft crash in 1957 when Trevor was just eight years old.

“It was an extremely tough time, as you can imagine,” Trevor reflects. “My mother was left with two children and I was at a very nice school.”

Unable to afford his education after his father's death, Trevor's future seemed uncertain until a scholarship opportunity arose at one of England's most historic educational institutions.

“I was able to get a scholarship to go to one of the oldest schools in England called Christ's Hospital, which was founded in 1552 by Edward VI as a charity school. It was basically founded for orphans and poor people on the streets in London,” he explains.

At this boarding school, now located in Sussex, young Trevor found a new path forward, starting at age 10.

“I learned what a holistic education meant. But most of all, I was inspired by two teachers at the school who encouraged me to follow my dream. And my dream was to be a farmer.”

This unusual ambition for a boy who had lost his father stemmed from the influence of his maternal grandfather, Mark Burgess, who ran a small dairy, cattle, and mixed farm. After his father's death, his grandfather ‘took me really under his wing. He was an extraordinary man,’ Tomkins recalls with evident admiration.

During school holidays, Trevor would work on his grandfather's farm, learning the practical aspects of agriculture while absorbing deeper lessons about business ethics that would guide him throughout his career.

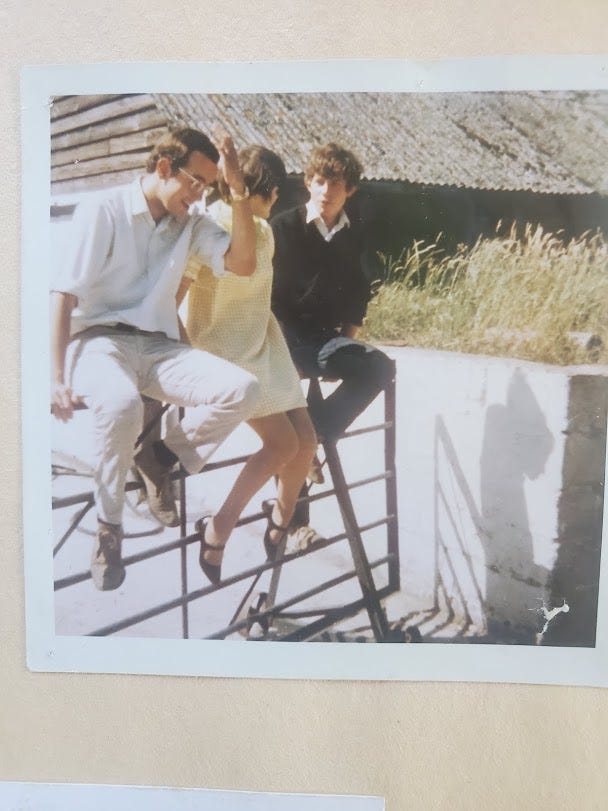

Determined to follow in his grandfather's footsteps, Tomkins secured a place at Reading University, then one of the UK's top agricultural schools. But once there, he was told that ‘the University aims to produce scientists and business people and if you want to be a farmer go to the farming college down the road’ He then had a dilemma but decided to stay!

Trevor completed his degree in agriculture and went on to earn a PhD in animal science—academic credentials that would later prove invaluable in his business career.

His expertise in animal nutrition, particularly dairy cattle, would become the foundation for his career successes.

Milk Specialities Company

After earning his PhD in animal science, Trevor built a career applying scientific knowledge to practical dairy farming.

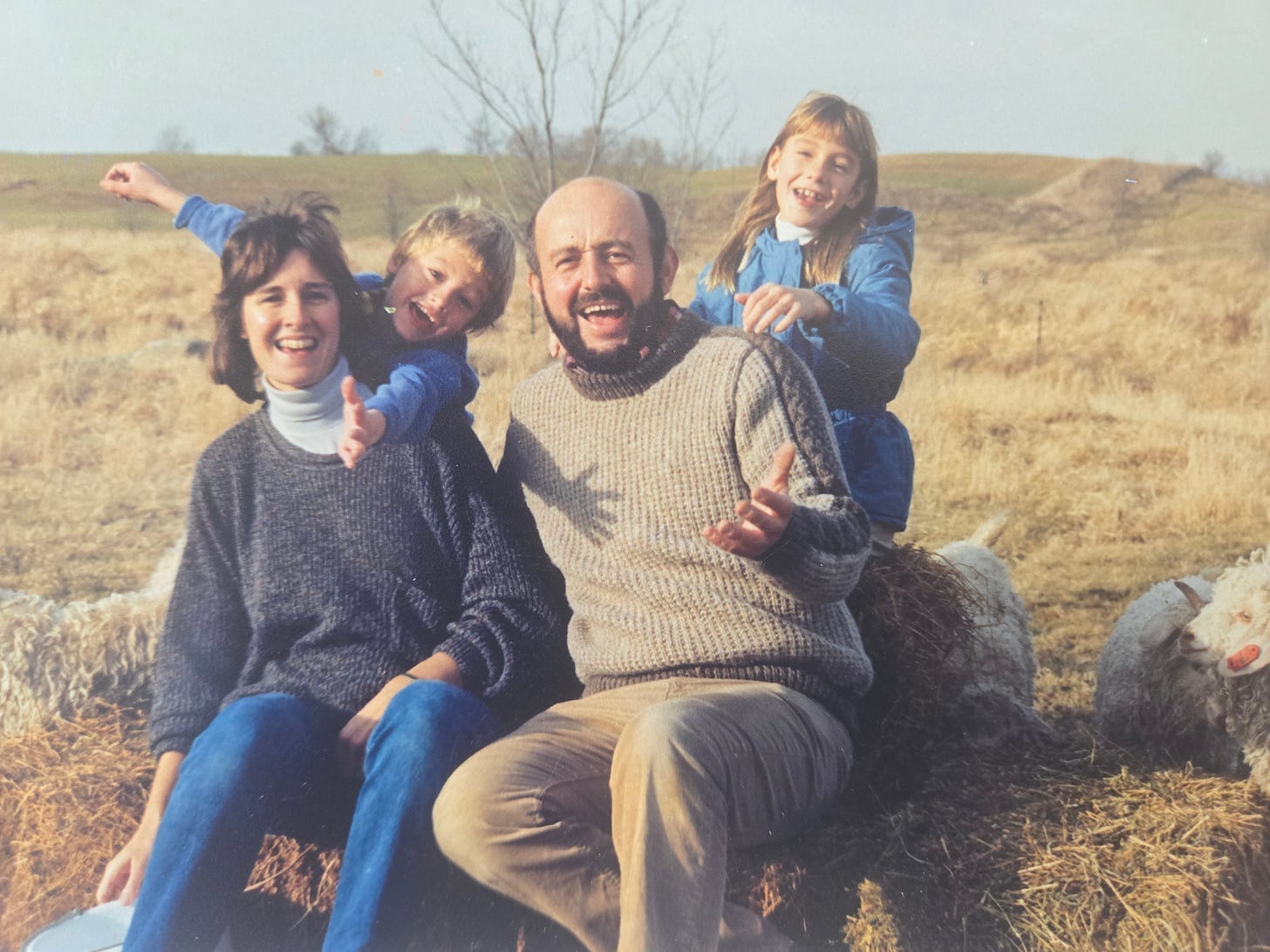

In 1983, while working for an English company (Volac Ltd), he was sent to the United States for what was supposed to be a one-year assignment to help set up the American business. That temporary position in Beaver Dam, a small community north of Madison, Wisconsin, would change the trajectory of his life.

Trevor recalls, “We had a two-year-old son, a four-year-old daughter, and my wife. And we thought this would be an interesting adventure. So off to America, we went.”

Among his early contacts was a company called Milk Specialties, which became one of his first customers.

When his one year was nearly up, Milk Specialties made him an offer. “They said, why don't you come and join us? We think you'd enjoy being part of our company and we'd certainly enjoy you being part of Milk Specialties.”

By 1985, with a green card in hand, Trevor joined Milk Specialties as head of research and technical services.

“I brought quite a lot of novel technology from Europe, from England, particularly related to animal nutrition and calf nutrition. And I had a lot of fun,” he says.

His innovative products helped the company grow until it was sold to an investment group with ‘fancy ideas of taking the company public’.

“Under new management that understood balance sheets but not products, the company began to falter, making ‘very silly decisions’ and ‘two very stupid acquisitions’—a pet products company they knew nothing about and a competitor whose customers wanted nothing to do with Milk Specialties.”

From 1990 to 1996, the company struggled increasingly until reaching a crisis point. The CEO instructed Trevor to lie to the board about FDA approval for a product—a demand that triggered the ethical stand described earlier.

After becoming president in 1996, Trevor implemented a transformational strategy based on fundamentals. His business philosophy, tested in the crucible of Milk Specialties' near-collapse, yielded extraordinary results:

From $53 million and losing money in 1996 to $95 million in sales by 1999

Reaching $140 million in sales by 2006

Exploding to $500+ million in sales by 2011

This remarkable 10x growth over 15 years came from three principles that echoed his grandfather's wisdom:

“We focused on three things: making sure that our customers loved us, looking after them all the way; making sure our employees were happy, that they felt motivated, they felt part of the company; and making sure that our suppliers felt that we treated them very fairly.”

Trevor's approach to understanding customers was methodical and scientifically grounded.

“I think I was very fortunate with a strong technical background and already a great relationship with most of our key customers. And they were very supportive. They recognized the dilemma that I was in.”

He explains the distinction that many businesses miss:

“I think that I was fortunate to understand the difference between marketing and sales. A lot of people don't understand the difference, but they're very different disciplines. Marketing is a discipline about understanding what the customer wants and then helping basically produce products or help the company produce products that the customer wants. But then sales are about getting a customer to buy the product. Very different.”

With this clarity, he rebuilt the leadership team.

“I hired a head of marketing and we began to change the focus of the company. We began to really focus on products that we knew were going to be successful in the marketplace.”

His science-based approach was another differentiator.

“I recruited some of the best academics from around the country to come and help us. So we met three times a year. And all I wanted to do was focus on the science. I did not want to focus on just the glitz of marketing or the glitz of sales, but focus on building products that would make the customers money.”

Trevor’s Most Valuable Lesson

“The most valuable lesson I probably ever had in my life was from my grandfather—always leave half a sixpence on the table,” Tomkins says.

A sixpence was a British coin, and this philosophy of never extracting the last penny from a business deal would become foundational to Trevor's approach to business.

This philosophy became vivid through his grandfather's actions at cattle markets:

“When he went to the markets in the spring, he would go up to the people selling the cattle and say, ‘That's a very nice looking cow. How much do you want for it?’ And the man would say, ‘A hundred pounds.’ And my grandfather would say, ‘I think it's worth more than that. I'll pay you a hundred and ten pounds.’ And the man was delighted.”

“In the autumn, when he went to sell the cow, a buyer would come up to him and say, ‘Mr. Burgess, that's a very fine-looking cow. How much do you want for it?’ And my grandfather would say, ‘Well, how much are you willing to pay?’ And he would say, ‘A hundred and fifty pounds.’ And my grandfather would say, ‘That's too much. A hundred and forty pounds will be enough.’”

The result?

“What that did is it built this incredible loyalty of supplier and customer,” Tomkins explains. “I have seen so many greedy people in business that want to drive the last rupee/dollar out of the deal. Business must be about win-win, that you leave the table happy and I leave the table happy.”

This counter-intuitive approach—sometimes paying more than asked and accepting less than offered—created relationships that sustained his grandfather's business through difficult times.

“At times, business was hard, things were tough. But he would always be looked after by those loyal suppliers and loyal customers. Very valuable lesson.”

This wasn't just talk. When acquiring a bankrupt competitor for Milk Specialties, Trevor applied the principle of building relationships with the vendors and suppliers of the target company.

“We will pay you back the money that you are owed, although we have no obligation to do so. But we will do that because we think it's an important business philosophy,” he explained.

“Every one of those suppliers then became extremely loyal and helped look after us during tough times.”

Creating Wealth For Stakeholders

As the company stabilized and returned to profitability, its then-shareholders proposed a management-led buyout. Trevor recruited a financial team, and borrowed money from a close friend to ‘put some money on the table,’ and in late 1999, the deal was completed with management owning 10% of the company and new shareholders owning 90%.

From 1999 to 2006, the company continued its growth trajectory, increasing sales to about $135-140 million. At this point, another ownership transition occurred, with a new private equity group, Stonehenge Partners, offering the management team a compelling deal:

“If you stay as a management team for five years and if you grow the company to $500 million, we will increase your ownership to 40%.”

From 2006 to 2011, Tomkins and his team delivered spectacularly on this agreement, taking the company from about $135 million in sales to $500+ million.

“We happened to be in the right place at the right time,” Trevor reflects modestly. However, the results came from his deliberate strategy of diversification and value-added processing.

“We were able to take the technology that we had been developing for animal nutrition and take it into the human nutrition area. So we were one of the pioneers of producing very, very high-quality milk protein products. And we started supplying the domestic and international ingredient markets... and became major suppliers to some of the large nutritional product companies.

The synergies between these divisions created a competitive advantage:

“Each fitted well with the others. We built strong relationships with farmers and developed excellent connections with milk processors. We were able to purchase byproducts from milk processing and transform them into high-value products for the human dairy market.”

The company's physical footprint expanded in tandem with its financial growth:

“We moved from three manufacturing plants to four to five to six to seven and then eventually to eight manufacturing plants spread across the United States.”

By 2011, the Milk Specialties transformation was complete—from a failing $53 million company losing $3 million annually to a diversified dairy nutrition powerhouse approaching half a billion in sales, with management owning 40% of a vastly more valuable enterprise.

Today, the company is known as Actus Nutrition and is closing $1.5+ billion in sales.

Venture Dairy Enterprises

By 2011, with Milk Specialties valued north of $500 million and management owning 40% of the company, Trevor could have comfortably retired.

Instead, he took his grandfather's philosophy global, founding Venture Dairy with his then-CFO, and close friend, Mike Drennan.

“The management team that we had built, many of them stayed, many of them are still there running the company today. And then a number of us took our shares and sold them because we had a separate ambition and we wanted to do something to basically help the underprivileged in the world.”

Venture Dairy is an investment firm with a mission to help small farmers through sustainable dairy farming practices

“The firm will be looking for established businesses in the dairy and food production sector, focusing on companies with revenues between $5-60 million. Our investments typically range from $2.5-5 million per company, acquiring anywhere from 5% to 25% ownership stake.”

The firm brings more than just capital—it offers deep industry expertise, access to technology, and market connections.

“We said that we needed to understand the problems in emerging economies,” Trevor explains. “I personally don't like the word third world. I think we should talk about emerging economies. Or talk about the global south.”

He and Drennan spent years conducting firsthand research across Central America, Vietnam, East Africa, Southeast Asia, and India.

Their immersive research revealed stark realities:

“In Vietnam, we saw small farmers with one or two cows tied up in dirty barns with no access to proper nutrition or veterinary care. In East Africa, farmers were getting paid a pittance for their milk by middlemen who would then dilute it and sell it at a premium. In India, we found farmers with excellent dairy genetics but no knowledge of proper feeding or housing.”

What they discovered was a universal pattern:

“We saw this problem that was the same virtually everywhere. There is a disconnect between the small farmer and the marketplace.”

A key investment thesis for Venture Dairy revolves around creating market linkages that solve fundamental problems.

Venture Dairy made its first investment in India by backing Akshayakalpa Organic in 2013. Akshayakalpa is today India’s largest organic food company.

As Trevor observes, “Akshayakalpa, by creating market linkages for smallholder farmers, managed risk to give confidence to capital providers that this is an investment worth making.”

The partnership with Akshayakalpa flourished beyond financial investment:

“I went down and met Shashi Kumar (co-founder and now CEO) and immediately identified a person with whom I believe I could not only develop a very strong personal and professional business relationship but also a man that would be as good as his word.”

This approach addresses one of the most critical challenges for smallholder farms: access to capital becomes possible when stable market connections reduce investment risk.

Venture Dairy Solutions

Drawing on his lifetime in the industry, Trevor identified three critical pillars for transformation:

“One is identifying appropriate technology. The second is to understand that any successful business must have access to capital. And then the third is to have access to the markets. And there must be a sharing, not necessarily equal, but equitable along that value chain.”

For the first pillar—appropriate technology—this meant developing simple, cost-effective solutions:

“Instead of having those cows tied up inside dirty old barns, we could build nice, ‘modern, simple facilities’ that dramatically improve animal welfare and productivity.”

For the second pillar—access to capital—Venture Dairy looks to work directly with financial institutions:

“We could help work with banks, and local financial institutions to help them build their portfolios. Because most banks, financial institutions, don't understand the complexities of agriculture.”

He elaborates on why agriculture presents unique financing challenges:

“Agriculture is essentially still related to biological systems. And biological systems have risks associated with them. And the job of the specialist is to know how to manage that risk.”

And for the third pillar—market access—they focus on building sustainable connections between farmers and consumers:

“There must be a sharing, not necessarily equal, but equitable along that value chain.”

India Focus

After extensive global exploration, Venture Dairy decided to concentrate its efforts:

“We have restricted our focus lately to India. We believe that you can't be all things to all people. And very frankly, we would prefer to do something really well than several things not so well.”

This disciplined focus reflects Trevor's belief in thorough research before commitment:

“One of the things that I said seven, eight years ago was that I would not want to invest in any other company in India until I understood India. And now I think I understand enough about India to be able to talk with authority and to identify real opportunities.”

This geographic focus came partly from difficult experiences elsewhere.

“We actually had a bad experience in East Africa, in Kenya. We ran into widespread corruption. And so we pulled out of East Africa. Lost quite a lot of money there. But it was totally unacceptable to me to be involved in anything that required needing to bribe people.”

More recently, Venture Dairy has begun investing in Frontrunner Farms (FFIN), a Mysore-based agricultural venture co-founded by Trevor's son Nicholas.

The investment team now includes five experienced entrepreneurs apart from Trevor: Kevin Bellamy (former portfolio manager for Rabobank) and James Neville (former CEO of Volac Ltd and grandson of the founder Dick Lawes who was the person that asked Trevor to go to the US in 1983), Tom Utgard, formerly of Stonehenge Partners and one of the original shareholders in Milk Specialties in 2006, and Mike Drennan.

Global Opportunity

Trevor sees both crisis and opportunity in global food systems.

For India, where 220 million dairy cows produce a mere 2.5-3.5 liters of milk per day, he envisions a radical transformation:

“If we could get the average cow in India to produce 15 to 20 liters a day—five to eight times more—we could reduce the number of dairy cows from 180 to 50 million. And if we got down to 50 million, we could feed those 50 million cows properly, as opposed to trying to feed 180 million cows badly.”

The current inefficiency has environmental consequences too:

“90% of what the cow is eating is just maintaining its body weight and its body movements. What we call maintenance, only 10% is going into production. By contrast, In an efficient animal, 70% of the nutrition is going into producing milk and only 30% maintaining the animal.”

This stark difference represents both an environmental and economic opportunity. With fewer, more productive cows, resources could be used more efficiently while reducing environmental impact:

“Improved efficiency will dramatically reduce the amount of greenhouse gas produced per kilogram of milk produced.”

Trevor's analysis of India's dairy sector is comprehensive:

“The biggest single issue in India is that the dairy population is enormous, 220 million milking dairy animals. I don't think anybody knows. The average milk yield is 2.5-3.5 liters per cow per day. You can't take them down the roadside, have them grazing for a few hours on very low-quality forage by the roadside, with no water, temperatures in the high sort of 20s, 30s, even 40s in places, and expect them to produce milk.”

This observation turns into a call for fundamental reform:

“It's got to start with appropriate housing for the cows, appropriate nutrition, understanding that the cow is a ruminant and it's got to have what we call a total mixed ration.”

Beyond nutrition, he points to quality control issues that must be addressed:

“We've got to make sure that the cow is being managed properly, that it's not getting disease, that the milk is not being contaminated with antibiotics or more. So in India, as you know, a very large percentage of the milk is contaminated with antibiotics and other adulterants.”

The A2 Milk Controversy

Tomkins doesn't shy away from controversial topics in the dairy industry. One particular marketing phenomenon—A2 milk—draws his critique as emblematic of poor science misused for marketing purposes.

While respecting cultural attachments to traditional cattle breeds, he emphasizes that the industry must be grounded in scientific reality:

“I do understand that A2 milk is associated with desi cows and there is a huge attachment to desi cows in India. So I think that we've just got to be aware that the science is thin, but the perceptions are great.”

This is particularly problematic in India, where a massive market has emerged around the purported benefits of "desi cow milk" or A2 milk.

When asked whether products like ‘A2 ghee’ (clarified butter) make scientific sense, his answer is blunt:

“A2 is beta-casein protein. Ghee doesn’t have protein! The butterfat in ghee from A2 cows and or desi cows and regular cows is the same, there is no difference.”

He sees the trend as ‘a short-term hype’ rather than a sustainable business.

Instead of focusing on unsubstantiated A2 claims, Tomkins urges the industry to concentrate on what truly matters:

“We must focus on improved efficiency, which will dramatically reduce the amount of greenhouse gas produced per kilogram of milk produced.”

His focus remains on the nutritional value that dairy provides. Rather than getting caught up in A2 marketing claims, he sees better opportunities in value-added dairy products::

“Milk, whole milk, is one of the most nutritious of all products in terms of its ability to provide protein, energy and fat, energy and lactose carbohydrate. And it's an extremely valuable product. We must focus on the downstream products, the paneer, the curds, the yogurts, the butter, and the ghee. And now the growth of cheese, big opportunities for the dairy industry.”

Advice To Young People: Pursue Entrepreneurship

For young entrepreneurs, Trevor offers wisdom that transcends his industry.

“Never wait to be given responsibility. Just keep taking it until somebody tells you to stop. I have never, ever been told to stop taking responsibility.”

When identifying talent, Trevor has a simple but penetrating question:

“If I gave you a magic wand and you could wave that magic wand, what would you like to be doing in, say, five years?”

The answer reveals a critical quality he seeks:

“The people who say, ‘I would like to be doing this and this or I would like to learn this or this,’ were the first indication for me of the energy I was looking for. So my biggest factor is energy. Energy is very tangible. You can feel it. And if I can feel energy, that person has already got one solid tick by him or her.”

For ethics assessment, his probing question is equally revealing:

“What is the most difficult ethical situation that you have ever been put into in your career? And how did you handle it?”

The answer—or lack thereof—speaks volumes:

“If people said, well, I've never had a, no, I don't think I've ever had a difficult ethical situation, I would say they either had and chose to forget it or they didn't have, in which case they probably weren't really in what I would call a position of responsibility.”

When hiring decisions don't work out, Tomkins advocates for direct, respectful communication. He notes a surprising pattern in these difficult conversations:

“Interestingly, I think in most cases where I've had to let somebody go and I've talked to them, at the end of the conversation, do you know what they say? ‘Thank you. Being honest.’”

To the digital-first generation, he makes a passionate plea to consider the fundamentals:

“I would like to encourage young people to think carefully about what they want their lives to look like. So many young people today get sucked into a fast-moving world of technology and the Internet and the digital world.”

Instead, he urges them toward something more essential:

“One of the very basics is caring for the planet and caring for our soil, caring for our livestock, caring for our food production systems. Because we desperately need young people to be the caretakers and the visionaries who will help this planet produce the food that an ever-growing population is going to need.”

His final observation reveals why, at 76, he continues his mission:

“I can't think of anything more satisfying than entrepreneurship. The joy that comes from solving problems... It's a bit like why people want to go to arcades and play games. They want to win, they want to find solutions.”

If you want to get in touch with Venture Dairy and Trevor Tomkins, please write to us at banjan@tal64.com.