The Northpoint Capital Story

Sameer Brij Verma helped build Nexus into a venture investing powerhouse, backing Indian founders with global ambitions. Now he is beginning what he feels will be his swansong.

“There is no theme. It’s just first principle thinking with strong founders.”

When Mohit Kumar came to Sameer Brij Verma in March 2020 with plans to build a fitness platform for Ironman competitors, there was no wearables market in India. Consumer electronics from India meant assembly operations for global brands, not innovation. The idea of competing with Fitbit or Apple seemed preposterous.

When Gaurav Munjal wanted to democratize test preparation through online video courses, edtech barely existed as a category, and monetization was always a challenge. The dominant model was Byju’s—expensive tablet-based content sold through aggressive sales teams. Free YouTube videos as the acquisition model? Not as common.

When Vijay Shekhar Sharma was running a mobile recharge business called One97 Communications, digital payments in India were a fantasy. Credit card penetration was in single digits. Smartphone adoption was nascent. Building a payments ecosystem in that environment? Impossible.

Yet Sameer Brij Verma backed all three. All three created markets that initially didn’t exist.

This is Verma’s pattern: finding founders solving problems that don’t yet have markets.

The absence of a market doesn’t deter Verma—it energizes him. Because where consensus sees impossibility, he sees a better entry point. Where others see risk, he sees inefficiency in capital deployment. Where the crowd demands proof, he operates on conviction.

“To be non-consensus and right is the best thing an investor can do,” he says, channeling Peter Thiel’s philosophy from Zero to One.

“Non-consensus bets mean that they’re capital efficient because nobody else believes in it. So the founder has more room to innovate and solve the problem. And more importantly, once you solve the problem, money will come because…you solved the problem.”

The logic is simple:

If you’re the only investor who believes, valuations are reasonable. The founder has breathing room to build without constant pressure to hit arbitrary metrics. There’s no competitive pressure from other VCs flooding the space with capital. The company can develop at its natural pace until product-market fit emerges. And when it does emerge—when the market validates what the founder was building—capital rushes in at much higher valuations.

Five-Star Education in First Principles

To understand why Sameer Brij Verma thinks the way he does, you have to go back to the beginning—to five-star hotels in pre-liberalization India, to a childhood spent moving from city to city, to a front-row seat to India’s economic transformation.

Verma’s father worked as a hotelier for ITC and Oberoi, managing properties across India during the socialist era of the 1980s. For the first 18 years of his life, Verma lived in different five-star hotels—luxurious cocoons that exposed him to operational excellence, service quality, and human dynamics even as India struggled through license raj and economic stagnation.

“I had the opportunity to obviously change a lot of schools, and grew up in different cities. I pretty much had a fairly privileged life from that standpoint. I wouldn’t say that we were very well off or anything, but we were very well taken care of. Ended up staying in hotels. Hotels, as you can imagine, in the pre-liberalization era were very luxurious places to live, especially five-star hotels. So 11 out of 18 years kind of been in five-star hotels, living and growing up there.”

The experience shaped him in ways that weren’t immediately obvious. He saw world-class operations in a third-rate economy. He experienced excellence in service while the country languished in mediocrity. He watched his father manage complex businesses—coordinating hundreds of employees, maintaining standards, delighting guests, turning around properties—in an environment of scarcity and constraint.

And he saw India wake up.

He was ten in 1991 when economic liberalization hit. Old enough to understand the national conversation, young enough to be shaped by it.

“I do remember it because there was a lot of chatter at that time. I was about 10 years old when that happened. They were saying things like — the country was broke. We didn’t have any dignity. The country was surviving on loans. I think our hand was forced to open up the economy, but the good news is that it was done thoughtfully.”

The transformation was immediate and dramatic. Foreign brands entered. Consumer goods proliferated. Telecom networks expanded. The middle class started to grow. Within a decade, India went from socialist stagnation to capitalist acceleration.

Verma absorbed the lesson: ideology bends to reality. Markets work when given room to operate. Constraints force innovation. And fortunes are made by those who see change coming before it arrives.

His first encounter with the internet came in 1995, at a cyber cafe in ITC Maurya, where his father worked.

“They opened up a cyber cafe, and there were these machines, which are Silicon Graphics machines, and they opened up a cyber cafe. It was one of the first in the country. Pages used to take forever to load, but it was just like a very, very fascinating thing to see. Yahoo and Excite, and all these websites. I used to sneak in there and try and use the internet as much as I could. We were staying in the hotel, so it was easier.”

That early exposure to the internet—before most Indians had even heard of it—planted a seed. This technology would change everything. Communication would be instant. Information would be free. Businesses would be built in ways that were impossible before.

His parents reinforced the tech exposure by buying the family a desktop computer in 1992—a PC with no internet connection, just floppy disks and basic software.

“It wasn’t that we had a lot of money, but my parents did go out of their way to buy a computer in the early 1990s. You look back at life and say that there’s so much that you have to be grateful for.”

By the time Verma went to Illinois Institute of Technology in 1999 for electrical and computer engineering, he was already primed to recognize technological inflection points. The dotcom boom was reaching its peak. Chicago, where he studied, was a hotbed of telecom and computer networks innovation—Motorola, Lucent, and the infrastructure companies building the backbone of the internet.

“It was a very different experience to see what the US and India was. US was far ahead. You could see the dotcom boom taking place in the ground central. Illinois Tech is a very strong school on the telecoms and computer networks side. A lot of activity was happening across Chicago because you had Motorola, Tellabs and Lucent there.”

He learned networking, RF planning, and systems architecture. He saw Cisco become the hottest company in the world as everyone raced to build internet infrastructure. He watched capacity get massively overbuilt, only to be utilized years later when applications finally caught up to infrastructure.

“Cisco was the hottest thing on earth in the early 2000s. It was seen to be the thing that will connect everything. Now you look at Cisco, it’s a shade of itself because people overbuilt capacity, which only got used by 2020 or 2018-19. Use cases and the internet just caught up much later.”

The future always takes longer to arrive than predicted, but it arrives with more force than anticipated.

He graduated in 2003, right as the dotcom bust was bottoming out. His first job was as a network architect for American Wireless Broadband in Chicago, designing wireless networks using Motorola’s Canopy platform—a precursor to WiMAX. From there, he moved to UTStarcom, working on triple play technology that combined voice, video, and data over a single network.

When he returned to India in 2005, telecom was exploding. Wireless adoption was accelerating. Airtel was expanding. Reliance was entering.

The country was leapfrogging developed markets by going straight to mobile, skipping the wireline infrastructure phase that had dominated the West.

Verma joined UTStarcom’s India operations, then moved to Ericsson in Gurgaon. At age 25, he became one of the youngest solutions architects at the company—the Swedish giant that was the Goldman Sachs equivalent of telecom.

“The first mobile phone I ever saw was an Ericsson. So I always thought I wanted to work with Ericsson.”

As a Solutions Architect, he was responsible for stitching together complex systems—combining products from multiple vendors to solve telecom operators’ problems. It was puzzle-solving at scale, requiring deep technical knowledge combined with business acumen and client management.

And it exposed him to venture capital.

Our telecom customers kept asking: Are these startups that you are partnering with for your solution venture-backed? Are they stable?

“That’s when I began developing a fascination with people investing in these companies. I understood the technology, but I also started learning about business and finance. That’s when I kind of began leaning toward wanting to get into venture capital.”

This was 2006-2007. Venture capital barely existed in India. There were only four or five active funds. Teams were small—three to five people. They all wanted McKinsey consultants or B-school graduates with years of strategy experience.

Verma had none of that. He had telecom expertise and technical chops. But he wanted in.

“Nobody teaches you the venture capital business. I had no people to get me in. I just applied to a few places. Nobody was wanting to look at this. There were only five, four or five funds at that point of time. The big funds all wanted people who had done their B school, had been in McKinsey for a few years and then wanted to get into VC.”

His entry point came through Reliance Ventures, the venture arm of Reliance Capital. He knew them from his telecom work—Reliance had been a client at both UTStarcom and Ericsson. When they started looking for people to join the venture team in early 2007, Verma applied.

“I joined as the second person on the venture team. We were doing proprietery balance sheet investing in startups.”

It was 2007. The global financial crisis was one year away. Telecom was still hot. And Verma was about to learn the venture business from the ground up.

His first deal tells you everything about his technical foundation: E-Band Communications, a San Diego-based company building wireless backhaul technology. Instead of running expensive fiber optic cables to cell towers, E-Band used millimeter wave frequencies to wirelessly transmit gigabits per second of data.

“They were connecting different cell sites so that you didn’t need to run fiber optics to them. Instead of running optic fiber from site to site, you could just wirelessly backhaul all the traffic from one side to the core. It’s a San Diego-based company. We put in $3 million, it was about a $7 million round.”

The deal combined everything Verma knew—wireless technology, telecom infrastructure, capital efficiency, and technical risk assessment. It validated his ability to evaluate early-stage companies in complex technical domains.

2008

Then the world collapsed.

The 2008 financial crisis led to a decline in telecom investing for years. Credit dried up. Operators stopped deploying. Equipment vendors struggled, and EBand’s first customer, Clearwire, declared bankruptcy. Reliance Ventures had to completely pivot away from telecom.

“Once 2007-2008, the global financial crisis happened, we had to completely change our focus from only telecom investing to investing in other spaces.”

The constraint forced generalization. Verma couldn’t just do telecom deals anymore. He had to learn consumer internet, ecommerce, software, fintech—everything.

The crash course in cross-sector evaluation shaped Verma’s philosophy. He learned that domain expertise matters less than you think. That understanding founders matters more than understanding markets. That first-principles thinking works across sectors.

Paytm

Paytm’s journey was long and volatile. Verma invested at Series B in late 2009 when the company was doing ₹260 crore in revenue with ₹32 crore in EBITDA as a value-added services business. The payments thesis was speculative—mobile broadband was nascent, smartphone adoption was low, and digital payments infrastructure barely existed.

But Vijay Shekhar Sharma had a vision:

“He wanted to do things like gaming eventually. But he said those things will not transact until you do not have payments. And then he had a thought process on how he will build payments and how he will build a wallet for doing that.”

Paytm went from a recharge utility to a payments giant. The company raised at increasingly high valuations, eventually going public in 2021 at ₹1.5 lakh crore market cap.

Between 2008 and 2010, Reliance backed Yatra, Paytm, Tessolve Semiconductor, GreenDust, Pelago (Sam Altman’s first company), Suvidha, and Scalable Display.

And he learned it fast. Because in early 2010, Reliance itself hit financial trouble. The parent company’s balance sheet came under strain. The venture business contracted. Verma had to look for his next move.

Building the Non-Consensus Portfolio

The call came in mid-2011.

Nexus Venture Partners was looking to expand the team. Founded by Naren Gupta, Suvir Sujan, and Sandeep Singhal, Nexus was small, entrepreneurial, and doing something different—cross-border investing, backing Indian companies that could operate globally.

Verma knew Reliance was contracting. He’d spent four years learning the business but needed a real platform. When he met the Nexus team, it felt right immediately.

“They were doing cross-border, which was something that I was doing at Reliance, and they were doing India consumption. Those were two broad things that I was very excited about, and it was a small team. I like working in small teams.”

He joined in August 2011. He would spend the next 13 years and two months there—long enough to build multiple fund cycles, long enough to see companies go from zero to unicorn, long enough to develop a reputation as the investor who would write checks when no one else would.

The Paytm bet at Reliance had already demonstrated his contrarian instincts. Now at Nexus, with more autonomy and a mandate to find the next generation of Indian startups, Verma would refine his approach into something systematic.

The methodology wasn’t complicated. Find exceptional founders. Understand what they’re trying to build. Assess whether the market will eventually pay for it. Determine if this specific person can execute and win. Ignore TAM calculations that assume static markets. Ignore sector themes that constrain thinking. Focus on first principles and founder quality.

This is the core of Verma’s methodology: back people who have demonstrated the capacity to execute, adapt, and win. Give them room to iterate. Don’t panic when plans change. Trust them to figure it out.

The alternative—waiting for proof, demanding traction, requiring revenue before investing—yields safer investments but lower returns.

“I’m investing in companies when there is no PMF. There’s no product even in some cases and several of them weren’t even incorporated at the time of deciding to invest. You look at the thought process of the founder. And then you work with the founder. You don’t try to impose your will there.”

His role is to ask questions, not give answers.

“Building a company is exceptionally hard,” he says simply.

“Who am I to tell a founder what to do? Founders are much smarter than most people. Many people do that because they think that, because they’re giving them money, they tell them what to do. My job is not to tell them what to do. My job is to ask the right questions. And my job is to get them to think and to be reactive 20% of the time. And otherwise sit back and let them do what they have to do if they are doing the right things.”

The 20% reactive, 80% hands-off ratio is revealing. Most VCs invert this—constantly advising, steering, and constantly trying to add value through intervention. Verma’s approach is different. He tries to back founders who don’t need babysitting. He asks strategic questions that force founders to think through critical decisions. But he trusts them to execute.

Postman

How many developers in 2014 would have paid for an API testing tool?

Ask any venture capitalist back then to calculate the TAM for an API testing tool—total addressable market—and you’d be told that there is no TAM. APIs were infrastructure, invisible plumbing that developers dealt with as part of their jobs. The idea that someone would pay specifically to test and document them seemed absurd.

Yet a young founder named Abhinav Asthana was building exactly that—a simple tool that made it easier to test APIs without writing complex curl scripts. The product was free. A simple Chrome extension. Nothing fancy. But every month, almost 250,000 developers were downloading it.

Most investors saw a nice developer tool with no monetization path. Sameer Brij Verma saw something entirely different.

“I did some work on XML when I was in college. I knew it was buggy and bulky. This whole framework of REST was coming up — and it was elegant, and it was going to be the future. It was very clear. There were early talks about microservices, and here was a tool that was getting adopted every month. It was a free tool, but it was very clear that there was an opportunity for a new development process to become commonplace because APIs are by their very nature the way in which software talks to each other.”

The technical insight mattered, but what mattered more was the founder.

“And here was a very young founder doing that and getting enormous amount of traction around it and he was thinking about a product. Abhinav was (and is) just a phenomenal founder—very ‘first principles’ guy.”

The question wasn’t whether developers (or their employers) would pay. The question was whether Asthana could figure out a way to monetize the value he was already creating. The usage validated the need. The founder validated execution. The market didn’t exist yet, but Verma bet it would.

He led Postman’s seed round in mid-2014, making Nexus Venture Partners its first institutional investor.

Today, at over $5.6 billion in valuation, Postman is essential infrastructure for millions of developers globally. The market Verma bet on in 2014 is now worth over $1.3 billion, and his firm’s early stake is worth exponentially more than the entry investment.

Licious

Verma’s respect for founders is shaped by how obsessed they can be with the problem statement they choose.

Verma invested in Licious, the fresh meat delivery platform, in July 2015. The founders—Abhay Hanjura from insurance and Vivek Gupta from finance—had zero meat industry background but were obsessed with transforming India’s meat market.

“I could see that consumption patterns would change and there would be a need to create a platform which would take this deeply unorganized business of meat selling and make it more convenient and organized,” Verma recalls.

Licious built a supply chain-first business. They sourced meat directly, processed it in ISO-certified facilities, and delivered it fresh within 90 minutes. The obsession with quality led them to become the second company in India to receive ISO certification for meat processing.

The key question: Why would someone pay Rs 180 per kilo for chicken when they could get it for Rs 110 from a local butcher?

The answer was trust.

Licious built retention rates of 65-70%. Today, the company does approximately Rs 500 crores in annual revenue and is on track to hit Rs 2,000 crores and go public within 15-18 months.

Jumbotail

This philosophy stems from witnessing journeys like Jumbotail, where Verma led the first $2 million investment in March 2016.

At the time, India’s Kirana market was massive but deeply unorganized. Kiranas serve 93-94% of retail, but the supply chain was labyrinthine—brands to wholesalers to distributors to stores. Co-founder Ashish Jhina, a third-generation farmer whose family exported apples, had worked at BCG on supply chain projects. His co-founder, Karthik Venkateswaran, had served as a major in the Indian Army before Stanford GSB.

“There was no company when we met them,” Verma remembers.

“Their very first hire was somebody we recommended to them, and they only got into business in July 2016 for all practical purposes.”

The strategy tested investor patience. For five years, Jumbotail focused exclusively on one city and category. No multi-city expansion until 2021. Meanwhile, Udaan raised massive capital, expanded to multiple cities, and got into 10-15 categories simultaneously.

“It wasn’t easy for them to raise money,” Verma admits.

“But the founders are a force of nature in many ways. They just dug in and fought every single day.”

While Udaan became a $3 billion company, Jumbotail stayed focused. They built the lowest-cost, most efficient supply chain in the country for Kirana distribution.

Today, Jumbotail serves over 500,000 Kirana stores across 50+ cities with 250,000-300,000 active customers. GMV is around $500-600 million. They recently became a unicorn. Several cities are already EBITDA profitable.

“It’s not been an easy journey,” Verma reflects.

“It was one of the toughest journeys I’ve personally seen for any company. But all the credit goes to the founders in terms of how they fought.”

Infra.Market

This pattern of betting on “impossible” businesses extends beyond the obvious.

In November 2019, when Verma met the founders of InfraMarket, most VCs recoiled at the pitch: a B2B platform for construction materials targeting infrastructure projects.

The company was doing just Rs. 5-6 crores per month. The industry was notorious—cement cartels, unorganized middlemen, government bureaucracy. When Verma brought the deal to Nexus’s investment committee, the response was predictable.

“They didn’t have an easy time raising money,” Verma recalls. “This is a very strange space. It’s a very difficult and deeply unorganised business.”

But Verma saw what others missed. Aaditya Sharda and Souvik Sengupta—25 and 26 years old then—brought deep domain expertise from working in construction. One was strong in finance; the other excelled in operations and sales. Their insight was that every building material operated as an independent value chain, and they could aggregate it all.

“They wanted to start with a few products and build a multi-product platform selling their own brands, which the large companies in the world were doing. But nobody in India was doing it,” Verma explains.

“Other companies started off as a single brand. These guys started off more as an aggregator and then basically going backwards in the value chain and actually manufacturing these products themselves as private labels.”

InfraMarket started with ready-mixed concrete and sand—unglamorous products forming the backbone of infrastructure developers. They became the single supply partner for infrastructure projects, aggregating demand and owning the end-to-end supply chain.

Today, InfraMarket is on track to do Rs 25,000 crores in revenue by 2027. FY26, they are on track to generate Rs 500+ crores in profits. They’re preparing to go public in early 2026. They’ve become the second-largest ready-mixed concrete player in India, the largest AAC block company, and the top-3 tile manufacturers.

From Rs 6-7 crores a month to Rs 25,000 crores annually—all while remaining profitable through almost their entire journey. The company lost money for exactly two months during COVID, then went right back to profitability.

“There’s nothing fancy about them,” Verma says about what makes B2B marketplaces work.

“It’s day-in, day-out execution. Relentless grind is the moat. Every single day, you need to get up and execute. Your supply chain has to be really efficient, your manufacturing has to be really efficient. And you have to use technology in the process really deeply and understand how credit works.”

Ultrahuman

Consider Ultrahuman’s improbable trajectory.

Mohit Kumar started with a concept for an Ironman-style fitness platform. Then COVID happened. The company pivoted to go online. Then pivoted again. And again. Eventually, Kumar landed on continuous glucose monitoring wearables for metabolic health, then expanded to smart rings for sleep and activity tracking.

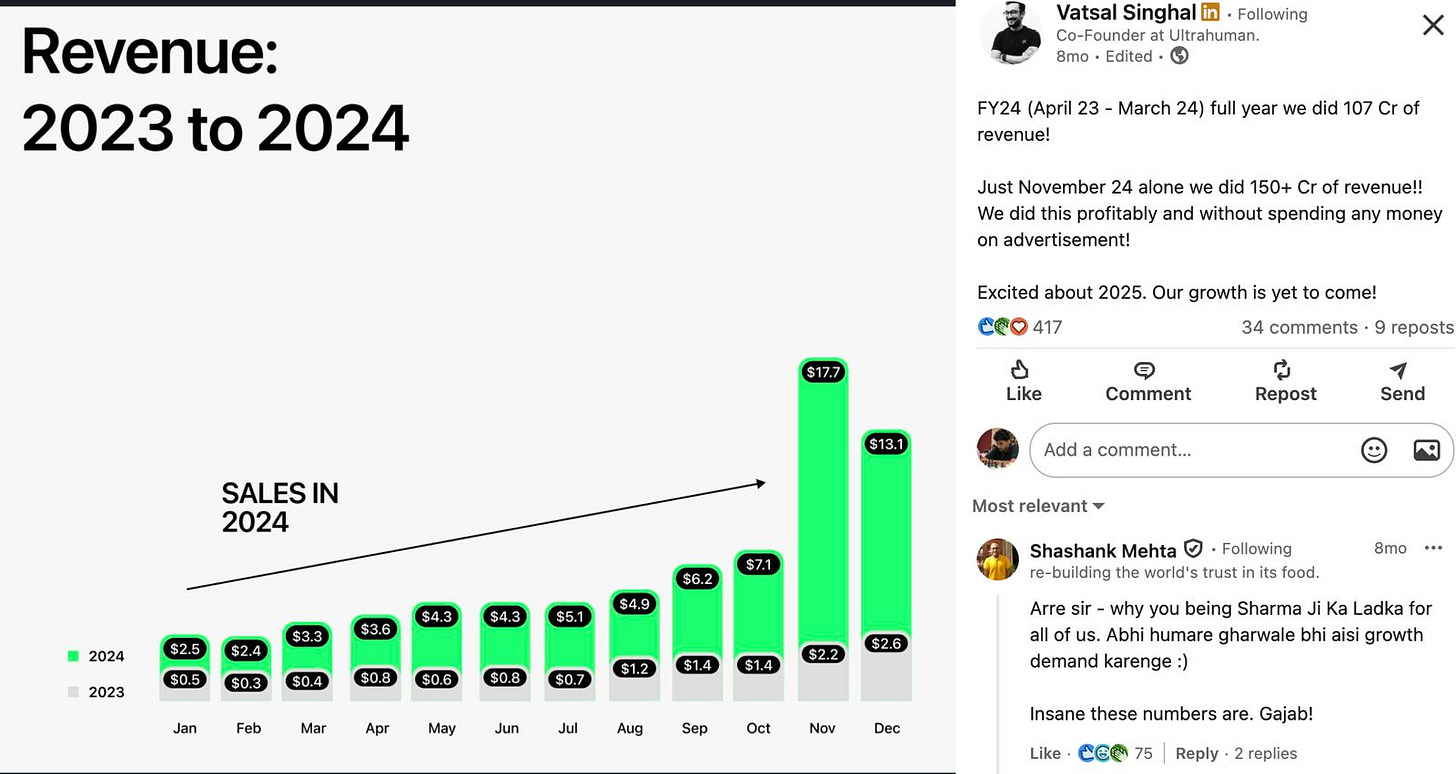

Today, the company sells globally in 50+ countries, with India representing just a small fraction of revenue. From zero to north of ₹1,400-1,500 crore in annual revenue and profitable in approximately 5 years. The product competes directly with Oura Ring, one of the hottest consumer wearables in the West, and holds its own on features, design, and pricing.

The journey wasn’t linear. It was chaotic, messy, full of dead ends and restarts. But that’s precisely what Verma backs—not plans, but the capacity to navigate chaos.

“Mohit Kumar is, simply, an exceptional execution person,” Verma explains, breaking down what he saw.

“He built a company before this called Runnr, which I had seeded. It didn’t work out because it was a hyperlocal B2B logistics business. When you’re a B2B business, you need healthy enterprises doing business with you. Unfortunately, all the customers died once the hyperlocal crash happened in late 2015/early 2016. So Runnr eventually suffered. Mohit went and merged the company with Zomato for 5% equity, giving all of us investors a very good exit. And then he joind Zomato as part of the process, which was a classified business back then, and got it transform into a transaction-led business. And he came from much behind in November 2017 and beat out Swiggy in under 24 months.”

Pause on that history.

Kumar built a hyperlocal logistics company that failed due to market dynamics beyond his control. Instead of walking away, he manufactured an exit that returned capital to investors. Then he joined the company that acquired his business and helped transform it from a restaurant listing site into India’s dominant food delivery platform, beating a much better-capitalized and entrenched competitor in the process.

Those aren’t business outcomes. Those are character indicators.

This is what Verma backs: not business plans, but the capacity to execute under fire, to pivot without panic, to build when others would fold.

“The characteristics of building, of executing at scale, of coming from behind—those remain. Those are the attributes that you have to back.”

When Kumar left Zomato to start Ultrahuman, the initial concept was fitness for serious athletes. It wasn’t a massive market, but it was interesting. Then the pandemic hit, and everything changed. Kumar iterated. He tried multiple directions—home fitness, corporate wellness, and health tracking.

Nothing immediately worked.

But he kept moving. He explored continuous glucose monitors for tracking metabolic health. The Indian market was too small. He went global. He iterated on wearables, eventually landing on smart rings.

He got the timing right on a category that was just emerging. He built the product, the brand, and the distribution. Today, Ultrahuman operates in 50+ countries and has revenue approaching ₹1,500 crore while being profitable.

“Unless you know, and unless you can feel it, there’s no way to gauge it in the early days,” Verma reflects.

“People used to think this was a junk company. And everybody in the media used to say all these things. That’s fine. Everybody has their own prerogative.”

The media skepticism was real. When Ultrahuman first launched, tech journalists dismissed it as another wannabe fitness app. When the company pivoted to wearables, critics pointed to Apple and Fitbit as incumbents that couldn’t be beaten. Oura had already defined the category when they launched the ring and had a years-long head start.

Every rational analysis suggested Ultrahuman would fail. Verma ignored all of it. He had conviction in the founder’s ability to figure it out. And Gupta did.

This is the pattern that defines Verma’s portfolio. Find people with demonstrated capacity to execute, to adapt, to win against the odds. Back them when the idea is non-consensus. Give them room to iterate. Win massively when they crack it.

The alternative approach—waiting for product-market fit before investing, demanding TAM analyses that prove markets exist, requiring traction that validates business models—yields safer investments but lower returns. You’re buying into consensus at consensus prices. The investor has less ownership. The outcome, even if positive, is incremental rather than exponential.

Verma’s approach inverts this. High risk. High ownership early. Asymmetric returns.

Over 13 years at Nexus, this approach generated exceptional returns. The portfolio included some of the biggest outcomes in Indian venture capital. But the relationship with the platform was coming to an end.

Building Northpoint Capital

By 2024, Verma had spent 13 years and two months at Nexus Venture Partners. He’d invested across multiple fund cycles. He’d seen companies go from zero to several unicorns like Postman, Hasura, Infra.market, Unacademy, Jumbotail, and early leaders like Ultrahuman, Liquidnitro, and Rocketlane. He’d developed a reputation as the investor who would write the first check when everyone else passed.

While at Nexus, Verma had helped build one of the most contrarian portfolios in Indian venture capital—Postman, Ultrahuman, and dozens of other bets that started non-consensus and became inevitable.

“Was there a payment TAM in 2009? There was none. What is the TAM for API development? None, right? What was the fitness wearable TAM out of India? There was none.”

Now he wanted to do it again. From scratch. With his own vision. Or as Verma puts it:

“I want to build the Founders Fund of India.”

Founders Fund, started by PayPal mafia members including Peter Thiel, Ken Howery, and Luke Nosek, became famous for contrarian bets on seemingly impossible companies: SpaceX (private space travel), Palantir (government-scale data analysis), Airbnb (sleeping in strangers’ homes), and dozens of others that were ridiculed before becoming inevitable.

The throughline wasn’t sector—it was audacity. Founders Fund backed people attempting things that conventional wisdom said were impossible. They wrote checks when everyone else laughed. They stayed convinced through years of skepticism. And they won massively when reality caught up to vision.

More importantly, both understand the concept that became central to Thiel’s philosophy and Verma’s practice:

“Competition is for losers.”

The phrase comes from Zero to One, Thiel’s book on startups and innovation.

“That’s my favorite part,” Verma says about that chapter. When did he first read it? “When it came out”—2014, right in the middle of his most productive period at Nexus.

The philosophy is simple but radical: companies that succeed create monopolies, not by blocking competition but by building something so valuable that competition becomes irrelevant. If you’re competing on price or features with dozens of similar companies, you’re fighting for scraps. If you’re building something genuinely new, you’re creating a market where you’re the only player.

Markets get created by monopolists who build products so good that they define categories. Postman created the API development tools category. Paytm created India’s digital payments ecosystem. Ultrahuman is creating the metabolic health wearables category.

“To be non-consensus and right is the form of investing I want to do,” Verma says, articulating the core principle.

“Non-consensus bets means that they’re capital efficient because nobody else believes in it. So the founder has more room to innovate and solve the problem. And more importantly, once you solve the problem, money will come because you solve the problem.”

The logic is elegant. Non-consensus means cheap entry, high ownership, and room to build. Consensus arrival means validation, more capital, and higher valuations. The delta between non-consensus entry and consensus exit is where returns live.

But executing this strategy from a new platform is hard. At Nexus, Verma had 13 years of track record, portfolio companies that validated his judgment, and relationships with LPs who understood his approach. At Northpoint, he’s starting fresh.

“I’m a no-name, nobody,” he says with characteristic self-deprecation. “So my work is cut out.”

The assessment is both true and false. True in the sense that Northpoint is a first-time fund without established brand recognition. False in that Verma himself is well-known among India’s startup founders as the investor who backed them when no one else would.

His strategy for the first fund of $155M acknowledges the reality:

“I think the first one, you do it with more sorted companies. You do a mixture of more experienced founders and young founders. De-risk where possible while maintaining the core philosophy.”

The Indian market makes this even harder. Unlike Silicon Valley, where power law outcomes can return entire funds from a single investment, India hasn’t yet produced many hundred-bagger outcomes.

“I don’t think the size of outcomes are still at that power law would work in the traditional sense,” Verma says.

This means quality has to be distributed across more winners. You can’t rely on one SpaceX to carry the entire fund. You need four to six solid outcomes that each return multiples of the fund.

The challenge is finding them. And here Verma’s approach creates an edge. While other funds chase hot sectors with visible TAMs, he looks for founders attempting impossible things.

The Venture Business

Venture capital attracts smart people who are used to being the smartest person in the room. They pattern match, they cite frameworks, they lecture founders on strategy. Verma does the opposite. He recognizes that founders are smarter than investors about their businesses. His job isn’t to tell them what to do—it’s to ask questions that help them think more clearly.

“Who am I to tell a founder what to do? My job is not to tell them what to do. My job is to ask the right questions. And my job is to get them to think and to be reactive 20% of the time. And otherwise sit back and let them do what they have to do. My job is to provide an intellectual honesty framework for effective decision making.”

The 20/80 rule—20% active engagement, 80% trust—inverts how most VCs operate. It requires confidence in founder selection, discipline in intervention, and comfort with uncertainty.

It also requires intellectual honesty about what works.

“Nobody teaches you venture capital, enterprise building. Whatever they teach you doesn’t work. If it did work, Harvard Business School would be able to reinvent itself. They’re out of their depth right now. McKinsey is out of its depth.”

The shots at Harvard and McKinsey aren’t random. Both institutions represent credentialism, pattern matching, and consensus thinking—exactly what Verma rejects. Business schools teach frameworks that worked in the past. Consulting firms apply playbooks from established industries. Neither approach works for zero-to-one innovation.

“The world is working with people who are supremely high-quality generalists and people who understand things, learn very fast with very steep learning curves and can look at things, look at the truth very, very clearly. They understand the truth, but they also are dreamers. So you have to live in a world of contradictions all the time. That’s what venture is. That’s what entrepreneurs are.”

The entrepreneurs he backs can hold two opposing views simultaneously. They’re pragmatic dreamers, grounded visionaries, disciplined risk-takers. They see reality clearly while believing in seemingly impossible futures. They pivot without panicking, iterate without losing conviction, and execute while adapting.

Finding these people is hard. Supporting them through the journey from ridicule to inevitability is harder. But that’s the job Verma has chosen. Again.

What matters more than fund size is deployment discipline.

“I don’t want capital to be a competitive advantage,” Verma insists. “The team and the execution, the platform, the product is great, then money will chase you.”

This philosophy runs counter to the capital arms race that defines modern venture. Funds raise bigger vehicles to write bigger checks to win competitive deals. Verma inverts this—he wants to be in deals where capital isn’t the differentiator, where the founder has room to build without constant pressure to deploy raised capital.

“Non-consensus bets means that they’re capital efficient because nobody else believes in it. So the founder has more room to innovate and solve the problem.”

The LPs backing Northpoint understand this approach.

The fund has raised from global LPs—“leading endowments and foundations and fund-of-funds,” Verma says. They have long-term horizons.

His expected win rate reflects this:

“If you’re a good investor, out of ten, four will work. If you’re a great investor, five will work. If you’re an exceptional investor, six will work. But you will have fatality. You need to have the stomach to absorb losses and take bold risks early.”

In India’s market, that means each winner needs to generate 5-10X to deliver overall fund returns of 3-5X.

It’s achievable but demanding. Unlike Silicon Valley, where one SpaceX can return an entire fund several times over, India requires distributed success across multiple portfolio companies.

“I don’t think the size of outcomes is still at that point where power law would work in the Silicon Valley sense,” Verma notes.

This makes founder selection even more critical.

This is different from Silicon Valley, where one investment can return an entire fund. Facebook returned Accel’s 2005 fund multiple times over. Uber returned Benchmark’s fund a few times over. Airbnb returned Sequoia’s fund a few times over. In India, those mega-outcomes haven’t materialized at the same scale yet.

“Even Sequoia Capital, which is one of the greatest funds in the world, 50% of the companies just don’t work out,” Verma notes.

“People misunderstand the asset class and the media currently does a poor job — like feeding on a founder’s miseries when things go south.”

The media criticism is unusually sharp for Verma. But it reflects a broader frustration with how Indian business journalism covers startups. Every failure gets dissected as a moral failing. Every layoff triggers think pieces about bubble dynamics. Every pivot gets framed as an admission of defeat.

This creates a risk-averse culture antithetical to innovation.

“If you’re just going to criticize every failure, nobody will try anything different.”

The observation is particularly relevant given Verma’s portfolio—companies like Ultrahuman that pivoted multiple times before finding product-market fit would have been written off as failures by media standards.

Supply Chain Moat - On Marketplaces and Brands

The question of brands versus marketplaces is particularly relevant for Verma, considering his experience backing them over the years. But in Verma’s mind, the differentiation boils down to how effectively a company can leverage its supply chain.

When Zepto attempted to launch their own meat business, they shut it down and returned to selling Licious. Why? Because fresh meat requires a supply chain excellence that a horizontal marketplace can’t easily replicate.

“Their business is not going into the supply chain of specific products,” Verma explains about quick commerce platforms.

“They’re trying to be everything for everyone. You have to invest in the brand. Otherwise, people will not buy it.”

The distinction matters: frequent-purchase commodities versus quality-premium planned purchases. Groceries, soap, toothpaste—marketplaces can win on convenience and price. But premium rice, craft spirits, quality meat, and premium luggage—customers want brands they trust.

“A category manager in an e-commerce company cannot invest and do all this stuff at the same level the way a company like Licious can,” Verma says. “The grunt is the moat.”

Therein lies the difference between B2B and B2C marketplaces, Verma explains.

“In B2B, there will be verticalized supply chains. So an Infra.Market can focus on specific products in their supply chain to build their private labels.”

In B2C, a single customer might buy a phone today, groceries tomorrow, and stationery next week. But in B2B, it’s one-to-one mapping. A Kirana doesn’t buy sarees or electronics—they buy food and groceries, and that’s their entire business.

“They’re running their business on you,” Verma says.

“They have a good amount of wallet share. They’re depending on you to sell through. So it’s a different need. And they only buy that one category.”

The AI Opportunity

On AI—the sector consuming infinite investor attention and capital—Verma is bullish on recomposition, skeptical of wrapper companies.

“The big foundational labs are going to win big,” he says bluntly.

“Everybody is competing with them. Everybody is building on top of them. The worst mistake is to be building on top of them in some ways and discovering very large markets. Unless you’re completely recomposing a business by itself end-to-end, just building something on top is just not going to be good enough.”

His focus is on companies using AI to fundamentally transform industries, including legal services, healthcare delivery, physiotherapy, and practice management.

“You take a business, any business in today’s market, and you’re changing that business completely using AI. That is not what OpenAI is going to do. They’re going to become a lowest common denominator platform.”

The example he uses is Harvey, the legal AI platform:

“Potentially taking a legal firm and completely changing how the workflow of a legal firm should work. And they’re using AI for doing that. OpenAI is not going to do that. OpenAI is not going to become an end-to-end legal firm.”

The distinction matters. Building a chatbot that answers legal questions using <insert LLM name> is a feature. Rebuilding how law firms intake clients, manage cases, research precedents, draft documents, and bill clients using AI is a business. One gets commoditized when LLMs launch new features. The other builds defensibility through workflow integration and proprietary data.

“You take a business and you recompose it with AI. You make it completely different and much more efficient with AI. There is an opportunity to transform any business.”

The India opportunity in AI, he believes, is in enterprise customization—taking general AI capabilities and embedding them in specific workflows.

“Every enterprise is different from the other. We Indians are smart people who can take and customize every business with AI. And that’s what we do with IT services. That’s what we’ve done for more than three decades now.”

The reference to India’s $200 billion IT services industry is telling. The country built that sector on exactly this capability: understanding complex business processes, codifying them, and improving them through technology. The AI era demands the same skill set, applied faster and more radically.

The Decade Ahead

Sameer Brij Verma likes zigging while others zag.

“Everybody says they want to back dreamers. What they end up backing is a US copy,” he says, describing the broader market.

The criticism is pointed. Most Indian VCs claim to want contrarian bets but gravitate toward validated models. Uber for X. Airbnb for Y. Netflix for Z.

Verma’s portfolio proves otherwise. There was no US comp for Postman when he invested—the company created a category. There was no Oura Ring playbook for Ultrahuman—they built in parallel. Paytm’s payments play preceded most developed market super-apps. Infra.market is a truly unique platform globally. Jumbotail started the whole eB2B wave globally in 2015.

The question isn’t whether exceptional founders attempting impossible things exist in India. They do. The question is whether Verma can find them before anyone else does, back them with conviction when everyone else laughs, and support them through the years of skepticism before validation arrives.

His track record suggests he can. Now he’s doing it again. From zero. With Northpoint.

“If I do my job well, I need to invest in six solid companies a year,” he says.

“I think there are six companies getting created every year that are exceptional. Am I able to find them and be in business with them? That’s my job. It’s as simple as that.”

If you have an interesting idea and want to connect with Northpoint Capital, reach out to us with your idea at banjan@tal64.com

Very insightful & tons of valuable nuggets here. Great work