The InfoBeans Story

How three friends from Indore built a ₹500 crore by revenue digital transformation company by staying together for 37 Years.

In 2008, InfoBeans landed a Fortune 500 data storage giant with a simple HTML website project worth $5,000. Mitesh Bohra coded the entire thing himself. It was static—not even a web application—and had to work across 48 different browser editions with strict W3C accessibility standards.

“Can you imagine how primitive that sounds today?” Mitesh laughs.

“But the requirement was that you had to hand-code everything. You couldn’t use tools because there were a lot of accessibility and other restrictions they had in place and no tool at the time was mature enough to accommodate this need.”

Seventeen years later, InfoBeans operates at the heart of that company’s operating system—the equivalent of Windows for the enterprise storage world. They’ve progressed from basic HTML to developing multiple releases of the core product that powers over 100,000 enterprise customers.

The account has generated multiple tens of millions of dollars over eighteen years. But that’s not the important thing.

“The important thing really is how we have progressed in terms of level of complexity,” Mitesh explains.

“They came to us in 2015, and the VP was like, ‘I know you don’t have this capability. It requires a whole bunch of C++ expertise. But I trust you guys so much that I want you to put together a 17-person team in two months.’”

By 2017, InfoBeans owned the entire product dev and support. And then the VP of Engineering—who has since become CEO—said something that the founders carry in their hearts to this day:

“If you want work done, go to InfoBeans.”

This wasn’t just a compliment. It was recognition of something that large Fortune 500 companies struggle with: institutional memory. Every two or three years, these organizations go through reorgs. People shift departments. Knowledge gets lost.

“They come to us because we provide that stability and longevity to them,” Mitesh says.

“New teams came on board who had no idea what they were getting into, even though the company owns these products. And they’re like, ‘Go talk to InfoBeans, they’ll know.’”

The same playbook worked even more dramatically with a global logistics giant.

Finding a Wedge

A leading logistics company headquartered in Germany provides logistics, courier, package delivery, and express mail services globally—it is a leading player in its market. It had an interesting problem with its ServiceNow bill—25% of its invoice amount was spent on its storage.

With time, the ballooning data was causing unbudgeted cost surprises. Even the archived data continues to add to the storage size. Large datasets negatively affect instance performance. The need for external platforms to access live ServiceNow data adds to the challenge.

Every enterprise running ServiceNow faces the same invisible problem: their database is growing, and so is their bill.

Audit logs. Email archives. Attachment histories. Years of accumulated data that nobody deletes because nobody knows what’s safe to delete.

ServiceNow charges by storage. The more data you accumulate, the more you pay. And for large enterprises running complex implementations, this “storage tax” can balloon into hundreds of thousands of dollars annually—money spent not on innovation, not on new features, but simply on keeping old data warm.

InfoBeans saw this pattern across their ServiceNow client base and asked a different question: What if you didn’t have to choose between keeping your data and controlling your costs?

The answer was Spacewarp.

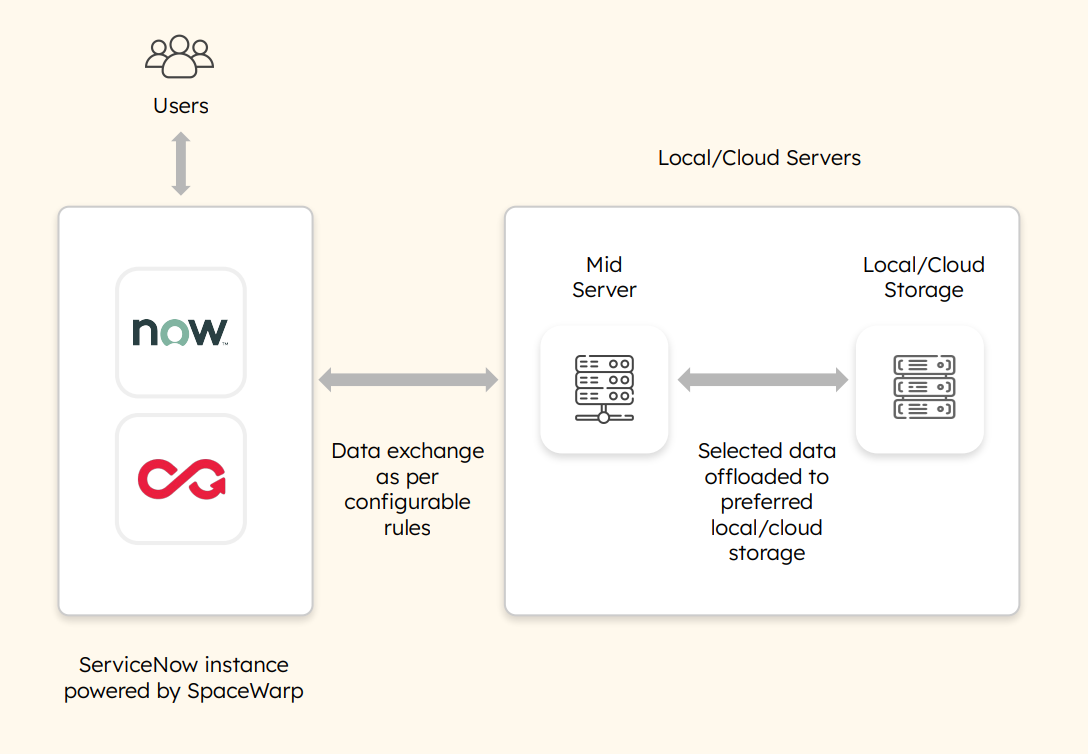

Spacewarp is deceptively simple in concept: it offloads data from your ServiceNow instance to your preferred storage while keeping that data accessible with a single click. No complex migrations. No data loss. No conflict with your existing ServiceNow configuration.

A smart scheduler handles the rest, freeing up ServiceNow instance data in just a few clicks.

But here’s what makes it remarkable: the offloaded data doesn’t disappear into a cold archive. It remains accessible through ServiceNow’s native interface. Users don’t even know the difference. They click, they get their data, they move on.

The Head of ServiceNow at the aforementioned logistics company said:

“Spacewarp helped us reduce incremental YoY database growth by ~70% and the initial data offload led to a significant cost offset, leading to less than 10 months of ROI on Spacewarp. The storage cost itself went down by 85%.”

“Its native ServiceNow UI and ability to plug into our highly customized instance with limited effort have enabled us to start reaping the benefits of database offloading very early after the license purchase.”

Spacewarp also illustrates InfoBeans’ broader strategy with platform technologies like ServiceNow and Salesforce. These aren’t just implementation services—they’re opportunities to build proprietary tools that solve universal problems.

ServiceNow has over 7,700 enterprise customers worldwide. Every single one of them has a growing database. Every single one of them is paying a storage tax. Spacewarp turns a common pain point into a wedge that opens doors.

“Newer technologies are client acquisition engines,” Siddharth explains.

“The bulk of the business comes when we custom-develop products with these organizations. But you need that entry point.”

An 80% cost reduction gets you in the room. What you build together with the client afterwards keeps you there.

ServiceNow was the entry point — simple IT service management support work that led to setting up a service desk. The logistics company wanted to expand its India presence and wanted a partner close to them. InfoBeans took an office in the same building, two floors apart.

“These days they (team members of the logistics company) actually end up utilizing some of our office space for themselves,” Mitesh notes.

“They just walk in as if it’s their own office, and that gives us immense joy.”

That service desk went from zero to 100 people in Chennai working solely on logistics company projects. Then came the expansion: SAP integration work. Product engineering. UX design with their design team sitting in Prague. Aviation services. Cargo divisions.

The numbers tell the story: 1000% revenue growth in roughly six years for this one client.

“That’s why when I say compounding effect,” Mitesh explains, “I talk about building a foundation that we built over all these years.”

This year, they cracked the company’s USA operations. Costa Rica is talking to them. The potential within just this one global enterprise is immense.

These two stories—one in Silicon Valley, one in Germany—illustrate InfoBeans’ land-and-expand strategy in action. Enter small, build trust, follow the customer wherever they want to go, and never let them down.

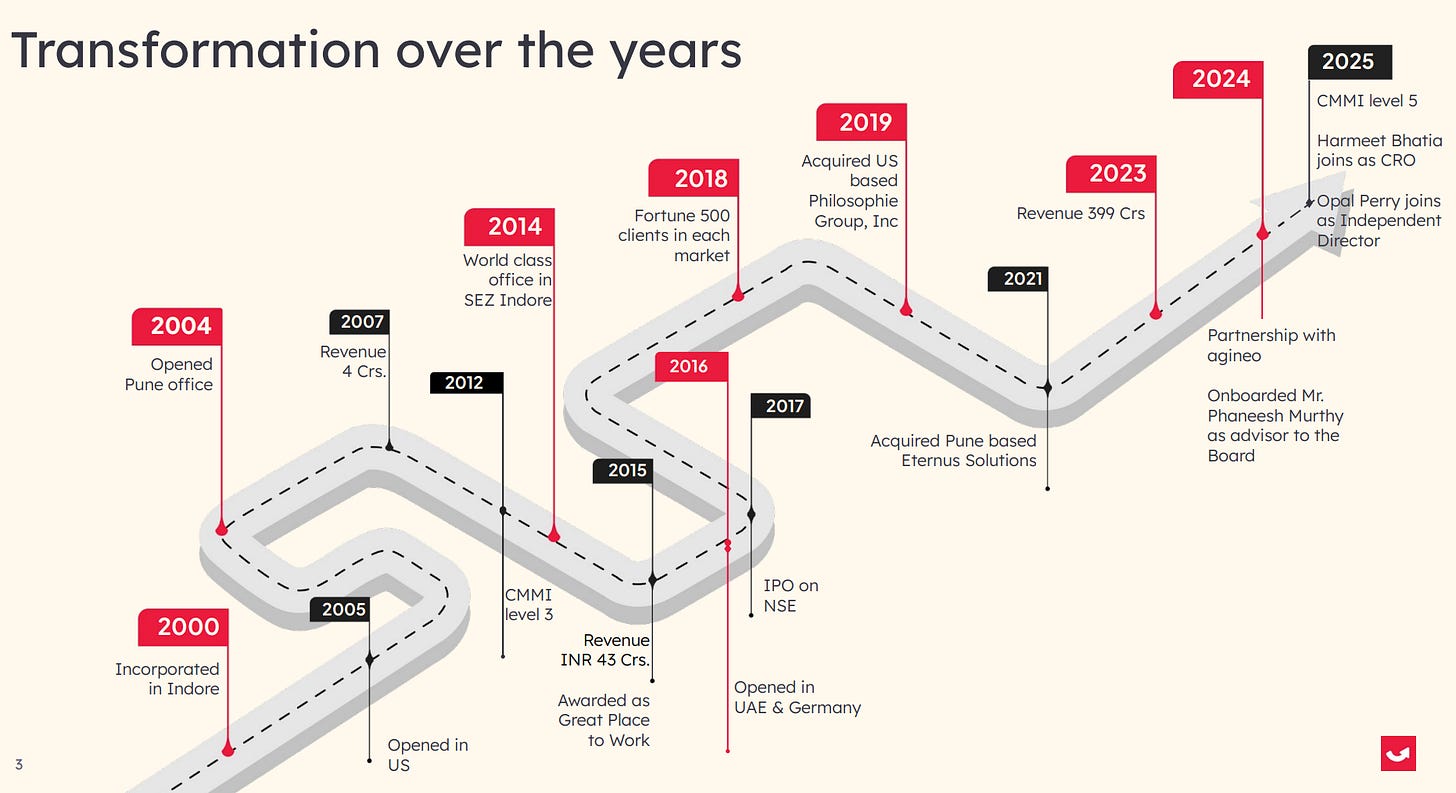

InfoBeans Technologies (NSE: INFOBEAN, BSE: 543644) was founded in 2000 as a passion project by three childhood friends working in the United States, who yearned for Indore, their hometown.

It went public in 2017 at a market cap of approximately ₹140 crores.

Today, the company is on track to surpass the ₹500 crore revenue mark with a PAT of 18%+. And the market cap is approximately ₹2,000+ crores. They have grown their revenue by 10x every 8 years.

But the most remarkable metric in their story? The founders have been together for 37 years, 25 of which have been spent building InfoBeans.

Indore, 1991

Five hundred students would gather every morning at 7 AM for coaching classes to prepare for state engineering entrance exams. There were no chairs. Everyone sat on the floor in a massive hall, while a single teacher taught all three subjects from a raised platform.

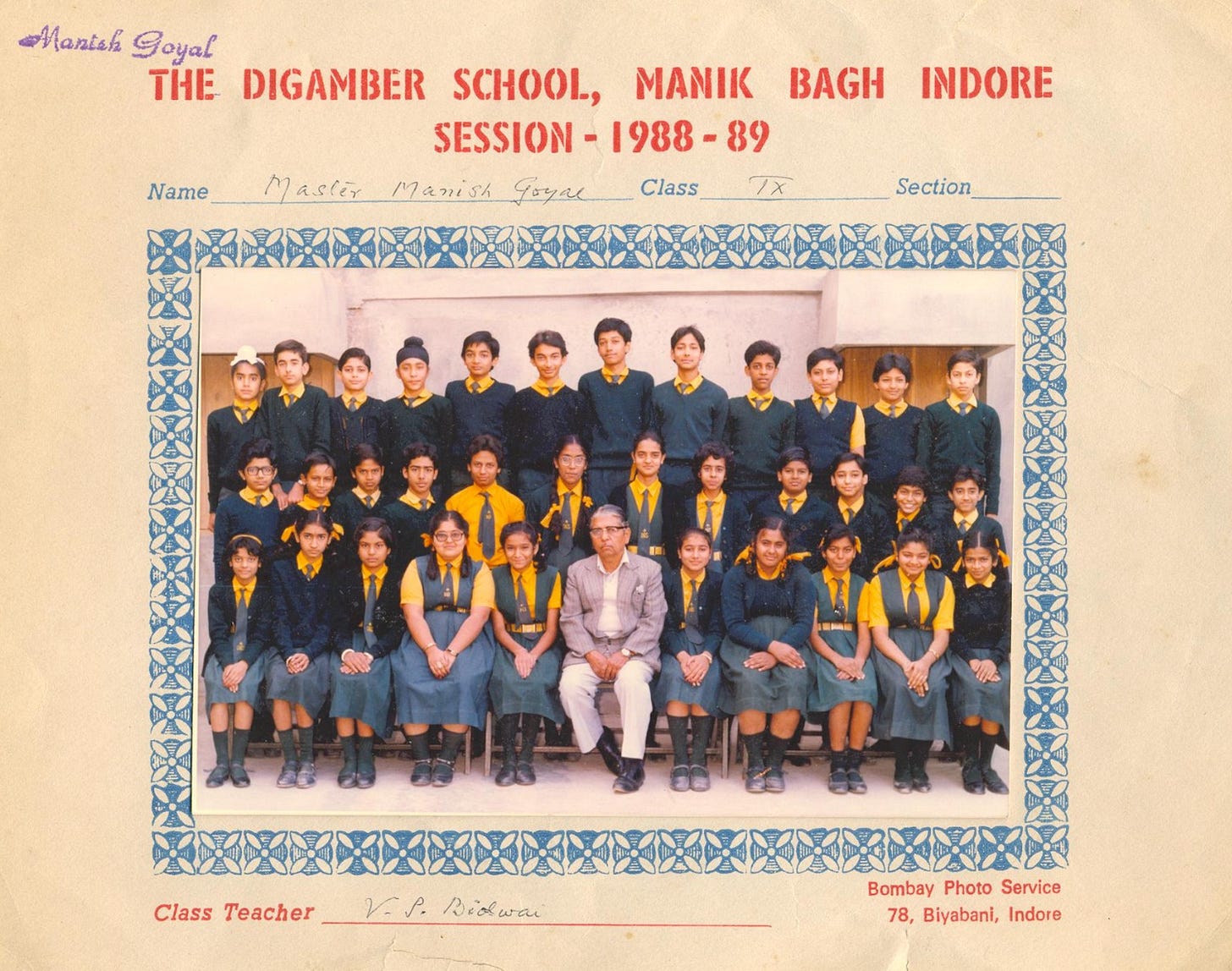

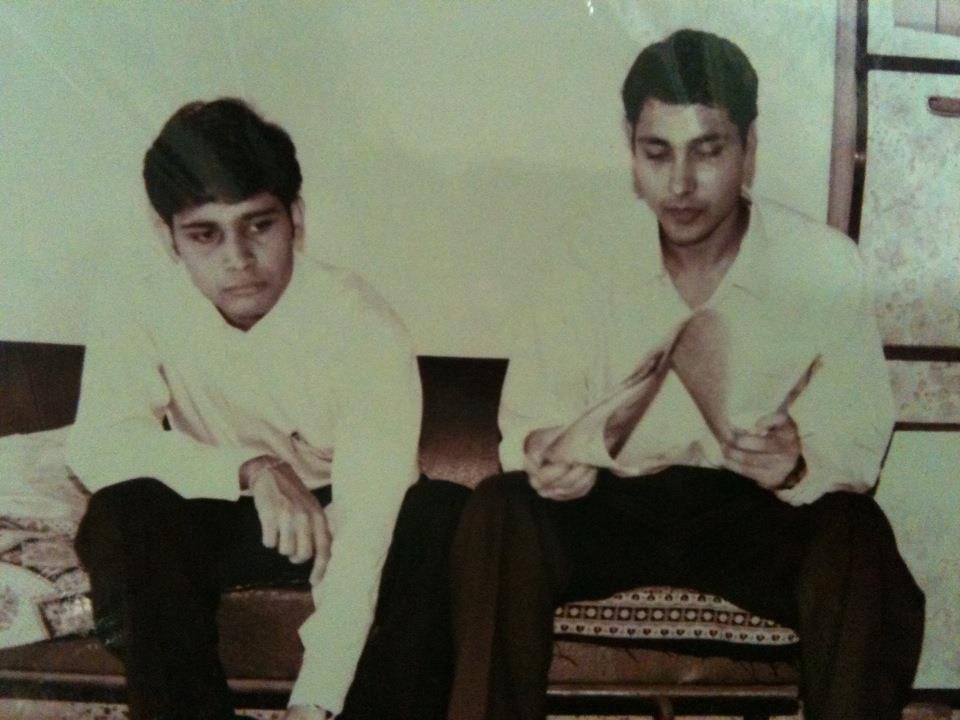

Avinash and Mitesh had known each other since ninth grade at The Digamber School. When their school didn’t offer PCM (Physics, Chemistry, Mathematics) for eleventh grade, both transferred to Tilokchand Jain High Secondary School. They lived about one and a half kilometers apart.

They would commute together—one bike, two people, sometimes two bikes, four people. In the mornings, Avinash would grab his father’s scooter and pick up Mitesh. They’d share rides to the coaching class, share notes, share anxieties about the future.

In 1992, all three cracked the state engineering entrance exam and got admitted to SGSITS, the only engineering college in Indore at the time. It was a year filled with social unrest in India, and their college exams were preponed—they got only two and a half months for their first semester.

But something else happened that year that would define their next three decades.

During ragging week, freshers were divided into two groups: Day Scholars and Hostlers. They were herded into a room on the top floor of the college building, asked their names, and their branches. When Avinash introduced himself—“Avinash Sethi, Electrical Engineering”—a senior noticed something.

“Wait. Siddharth Sethi from the Electrical Engineering was just here. Are you brothers?”

They weren’t related. Siddharth had studied at Daly College, a princely school. Avinash came from a more modest background. But from that moment on, they were known throughout engineering college as the “Sethi Brothers.”

By the third year, all three of them had made a decision that would shape their futures: they would prepare for the CAT exam together.

“We realized that with technology, we don’t need a lot of resources,” Avinash explains.

“We wanted to do business management. IIMs appealed to us.”

So began the morning ritual. 7 AM coaching class for CAT preparation. Then, because they couldn’t go home for lunch and didn’t want to carry tiffins to college (a “young fad,” Avinash admits), they found a bhojnalaya—a simple establishment serving fresh thalis—where they would eat at 9:30 AM before heading to college.

All three of them. Every day. Together.

“We used to learn from each other. Siddharth used to guide us on the grammar part. When we struggled, we discovered things and found solutions together. That is the process where you bond.”

Siddharth had lived in the UK until fourth grade. His English was impeccable, his math sharp. He had originally prepared for IIT—he even cleared BHU Varanasi while in college—but chose to stay in Indore with his friends.

For CAT, there were no testing centers in Indore. The three friends would travel to Bhopal together, take the exam together, come back together, and discuss every problem they solved and every mistake they made.

In 1996, none of them got through the MBA programs. All three received interview calls but couldn’t convert. All three felt devastated.

But they also felt something else: they couldn’t keep asking their parents for money.

“We were 21 years old,” Siddharth remembers.

“For the MBA preparation, we didn’t attempt any campus interviews. We started introspecting—where can we get a job?”

The IT industry was booming. Infosys had just gone public. Big companies were coming to their college, hiring in bulk. The entrance tests required reasoning and analytical skills—exactly what they had prepared for CAT.

Avinash cleared TCS. Mitesh cleared Tata Infotech. Siddharth had joined Tata Motors at Jamshedpur straight from campus and later transferred to their Mumbai IT division.

All three ended up in Mumbai. All three ended up in the Tata companies. None of it was planned.

Maximum City

Mumbai changed everything.

Avinash’s training was in Borivali East. Mitesh was in Andheri SEEPZ. They took an apartment together in Borivali West with some college friends—four people in a small space. After training, Avinash was posted in Cuffe Parade, a two-hour commute each way.

But in a stroke of what Avinash calls “destiny,” Siddharth’s office after his transfer was also in Cuffe Parade—directly across from Avinash’s building.

“I was in Maker Towers. Siddharth was in the World Trade Centre. We used to have lunch together every day at the Kamat’s.”

“Mitesh was with me in the apartment, sharing dinner. Siddharth was with me at work, sharing lunch. The common element never separated.”

They would meet every weekend at a park in Andheri West and sit on the same bench every time, dreaming about what the future would look like together. They didn’t know what or how, they just knew it had to be done.

‘Life mein kuch karna hai yaar.’ (We have to do something meaningful with our lives) was always the primary thought that they would brood over at that bench for hours. They would carry those thoughts as they went back home on Mumbai local trains in two different directions.

They were earning approximately ₹5,500 a month. Avinash paid ₹2,400 for rent and ₹450 for a first-class train pass. After food and other expenses, savings were negligible.

They didn’t care.

What Mumbai gave them was something their engineering college in Indore never could: confidence.

“Before Mumbai, I couldn’t even speak in English properly,” Avinash admits.

“Mumbai made me talk confidently. Mumbai changed all three of us.”

Getting to the office was a daily struggle. Missing a train meant losing a big chunk of time. Their apartment was on the fourth floor with no lift. If you forgot something while leaving, you couldn’t go back.

“You have to plan ahead. You have to think. Living in Mumbai builds these habits.”

The Gujarati tiffin service they subscribed to made everything too sweet. So they found a bhojnalaya at Borivali Railway Station and would eat there every evening before climbing those four flights of stairs.

It was during these Mumbai years that Avinash discovered Dale Carnegie’s “How to Win Friends and Influence People.”

“I used to read one chapter and see how I could apply it. I really found it miraculous—it really works. It changed me.”

But something else was brewing. They would calculate: TCS was charging $30 per hour for their services. They were being paid ₹5,500 per month. The math was not mathing.

And they were tracking Infosys—the only listed IT company at the time. Every morning, before leaving for the office, they would check the stock price in the Times of India.

“We used to track the story behind Infosys. We were in the same industry. There was so much excitement around that company.”

Then Mitesh discovered something. On one of his monthly trips to Indore—they were so homesick they went back every month, taking the Friday night train and returning Sunday night—he found a company that would train you in newer technologies and ship you to the US on an H1B visa.

The company was called Suvi Information Systems, a body-shopping IT firm based in Indore that was also trying to build a product for jewelry manufacturers.

All three quit their Tata jobs. They went back to Indore for training. Mitesh learned Microsoft Visual Basic. Avinash and Siddharth learned PowerBuilder.

In April 1998, Mitesh went to the US. Three months later, Avinash followed. One month after that, Siddharth arrived.

They landed in three different corners of America: Mitesh in New Jersey, Avinash in Los Angeles, Siddharth in Jacksonville, Florida.

“Our exposure, living and working in the US—that set some pretty strong work culture and work ethics for us,” Mitesh recalls.

“And having worked in different Tata companies, there is this degree of fairness and ethics that you carry. And then you come to America and you see how dedicated people are and how committed people are to their work. Timelines actually mean something.”

“We really thought we should bring a lot of these learnings to India. We thought we will inculcate some of these elements around passion, a sense of ownership, that whatever you deliver, you own. Something goes wrong, it’s your neck on the line. Something goes right, you let the team receive all the kudos.”

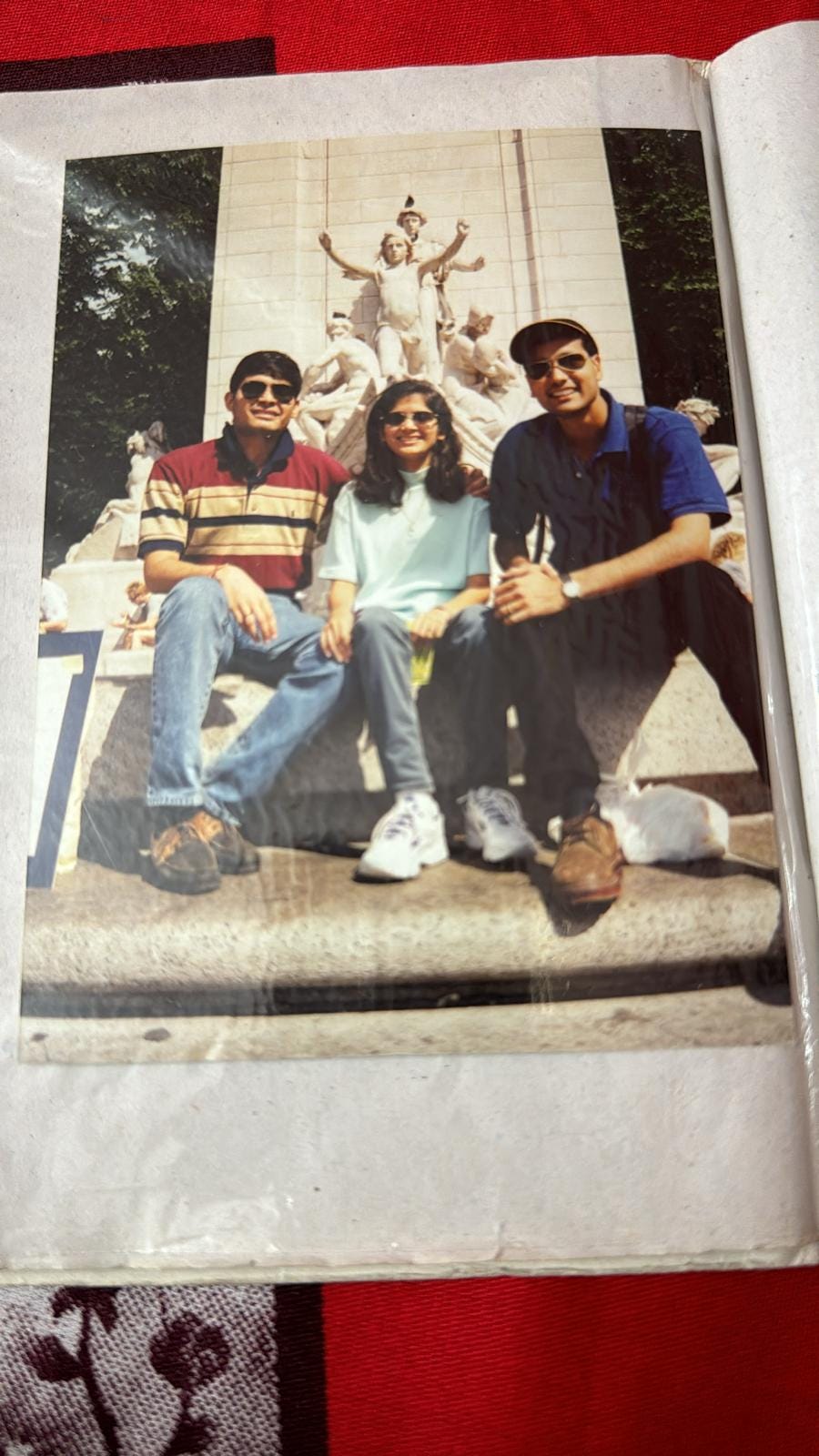

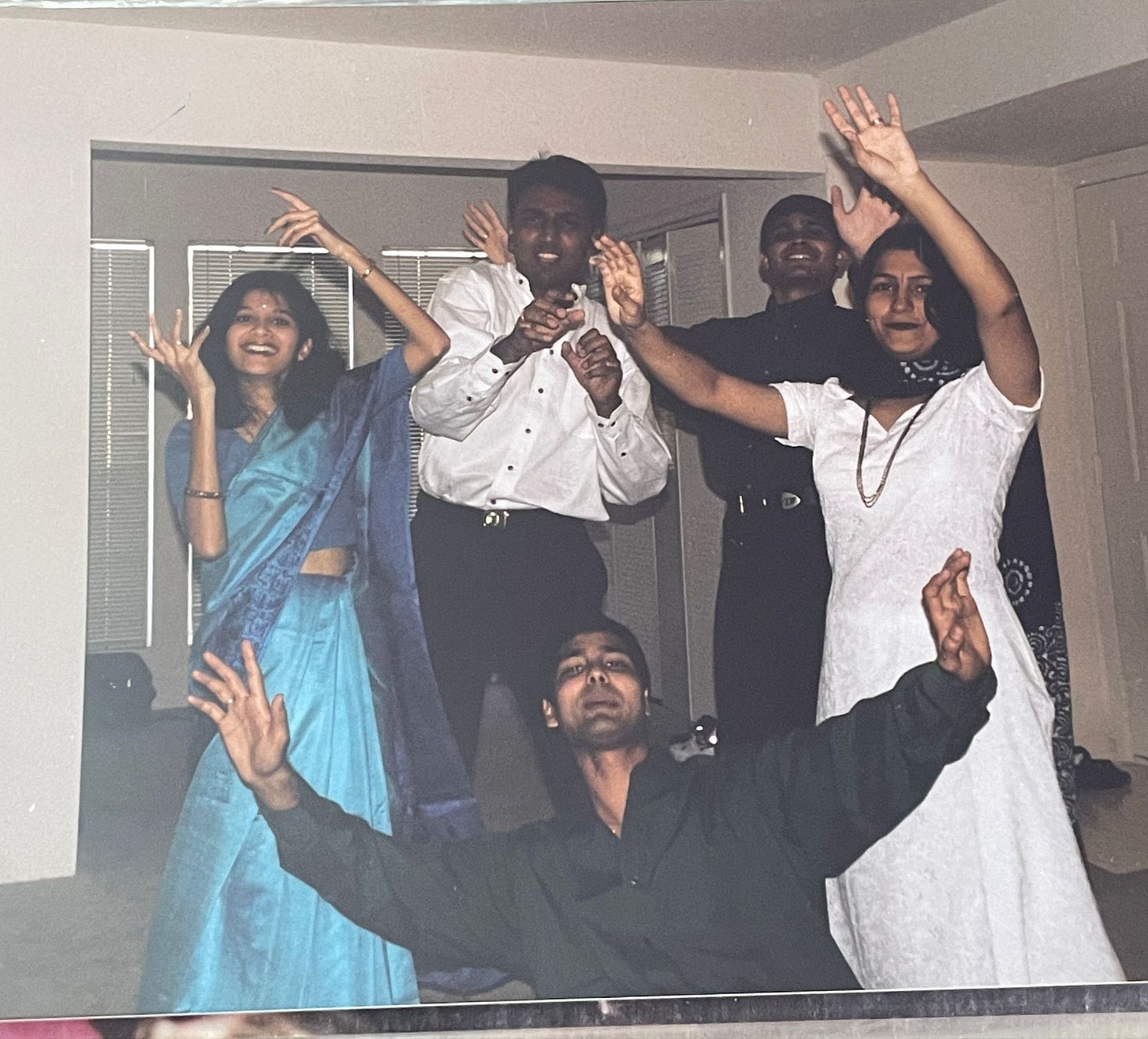

But they weren’t done being together. That Thanksgiving, Mitesh, his wife Priyanka, and Avinash flew to Florida. They met Siddharth and his wife Meghna—both Mitesh and Siddharth had gotten married just before leaving India, pressured by their families who worried about them surviving alone in America.

Five people. One road trip. Ten days. Orlando, Disney World, Miami, Key West.

“That is when we thought it’s time to build something together, remembering our moments on the bench in Andheri,” Siddharth says.

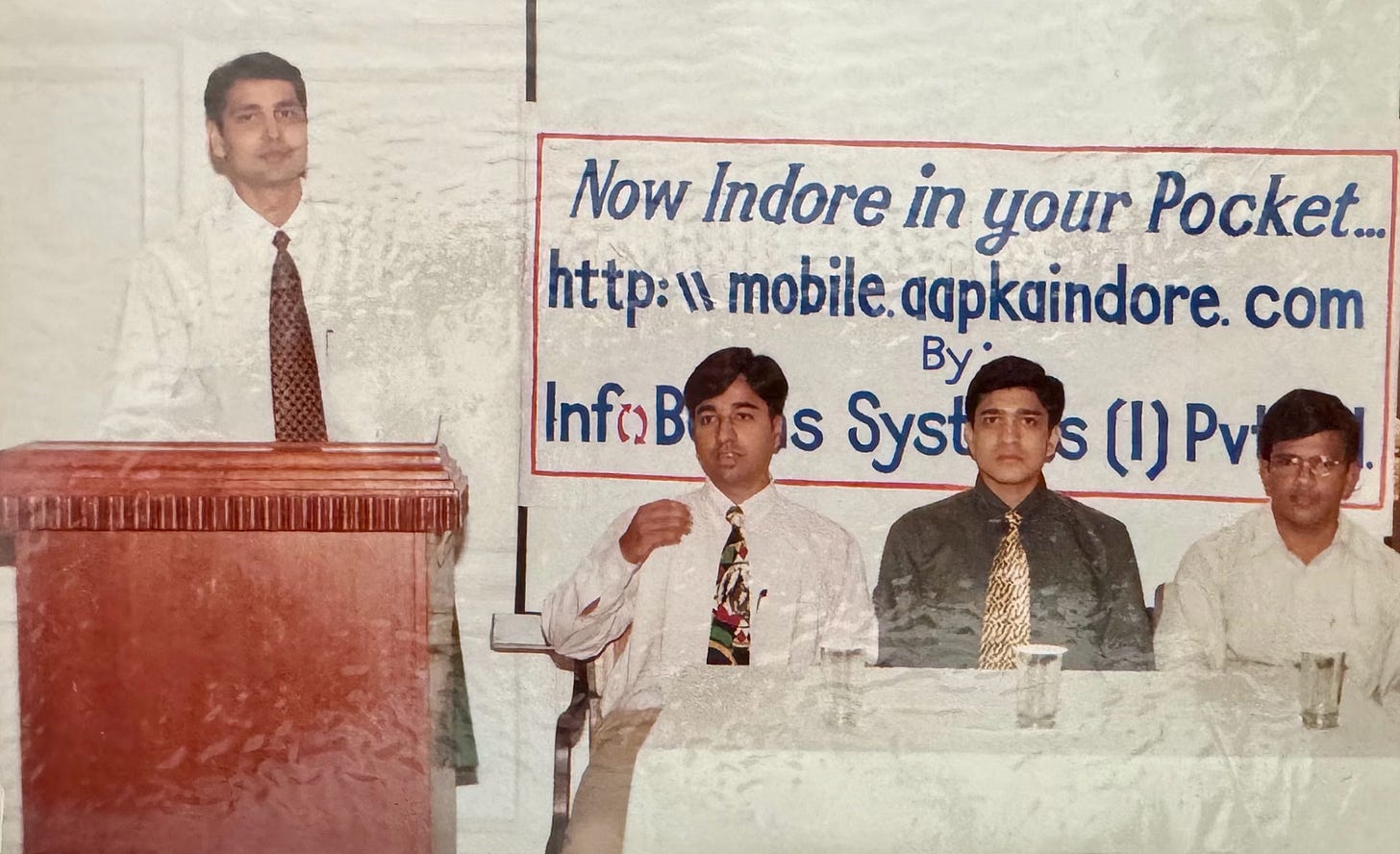

aapkaindore.com

“We all happened to be from Indore. We were missing Indore partly,” Avinash recalls.

“And we were also trying to look around people in the neighborhood who also belonged to Indore.”

The browser had just arrived. The internet was transforming from a text-based curiosity into something visual, something you could build things on. And in November 1998, somewhere between Disney World and Key West, an idea crystallized.

“We said okay, let’s do something together. For Indore. Not from Indore, but for Indore.”

The three engineers-turned-consultants taught themselves HTML, stylesheets, and JavaScript on weekends. Meghna, Siddharth’s wife, who had just completed a graphic design course, created the visuals. They scraped the early internet for addresses and phone numbers of people from Madhya Pradesh, building a directory of 500-1,000 names—the first “friend search” for the Indori diaspora.

But they didn’t stop there.

They hired Priyanka’s cousin, Paridhi, in Indore. Her job was unusual: she would go to famous stores across the city, photograph their products, and upload them to the website. Bouquets. Chocolates. Greeting cards. Suddenly, an NRI in New Jersey could send a birthday gift to their mother in Indore with a few clicks.

“We created a free postal service. You write an email to us, we’ll print it and courier it the same day. It reaches your relatives or friends within 24 hours.”

The business model was unique in 1999. They were paying 9% per credit card transaction to CCNow—there was no PayPal yet, no Stripe, no infrastructure for what they were attempting. But people paid anyway.

“We used to get letters from them,” Siddharth says.

“They would write: ‘We have not been able to send Rakhi to our brothers or sisters for years. Because of this platform, we can do that now.’”

March 1999. The platform launched. It became self-sustaining within months.

More importantly, AapkaIndore.com became their showcase. Proof that three friends working weekends from different time zones could build something real, something that worked, something that served a genuine human need.

Birth of InfoBeans

By late 1999, an apkaindore.com user based out of the US called the team to work on a project. But to start something like that, they couldn’t do it while being fully employed in their jobs. They had to set up a development center in India.

The timing was audacious. The Y2K scare had made IT services incredibly lucrative. Everyone was making money hand over fist. Walking away from the US just as the party was getting started seemed insane.

But Avinash was never really at the party. He was in Portland, working with Intel Corporation by then, watching the dot-com boom from a distance. The entrepreneurial itch had become unbearable.

In November 1999, he returned to Indore.

“I came back, and we started InfoBeans from my home garage,” he says simply.

The initial capital was $9,000—$3,000 each from the three founders. At that time, there was no formal partnership. Mitesh and Siddharth were still in the US, working their jobs, contributing capital and moral support.

The aforementioned Aapkaindore.com user gave them their first project: a simple website development job for a company called Ship Methods for for $1000.

First year revenue: ₹15 lakhs. First year profit: ₹5 lakhs.

“So we almost made back the $9,000 we invested,” Avinash notes.

“That money was never consumed—we reinvested it.”

“From that day onwards, we have always chosen to reinvest the money in the business. We have not taken a very hefty dividend at any point in time.”

Then the dot-com crash happened. March 2001. The NASDAQ collapsed. The Y2K party was over.

But InfoBeans was a micro player. The crash that devastated Silicon Valley barely touched them.

Avinash attempted to expand into the UK, establishing InfoBeans Limited there and applying for his work permit.

He flew to London on September 10th, 2001.

On September 11th, he watched the Twin Towers fall on television.

“That was another wipe-off,” he says quietly.

However, during the same flight from Delhi to London, Avinash met a Sri Lankan lawyer who mentioned that his son worked in IT. Would Avinash like to connect?

The son’s name was Kevin Rochey. He was based in London. He liked what InfoBeans was doing. He became a client.

“Just a chance meeting on a flight got us work,” Avinash marvels.

“Services are all about trust. There has to be a certain amount of trust created for you to get work.”

This would become the core philosophy of InfoBeans.

Growth Momentum

The job market in the US became quite unstable following the September 11 attacks. Siddharth returned to India in 2002, having been laid off from his startup in the US. By 2004, Mitesh had returned to India from the US for good. Now, all three founders were working full-time on building InfoBeans.

By then, InfoBeans had begun facing a problem that would have been unthinkable in Bangalore: they couldn't find talent in Indore. Their solution was counterintuitive. They started InfoBeans Education Services, training people in Java and Microsoft .NET, then handpicking the best graduates to join the company.

“We had education services in Indore, Pune, and Bhopal,” Siddharth recalls.

“Interestingly, in 2005, we were making more money in education than in IT services.”

But the education business had a fatal flaw: it wasn’t scalable. Unless the founders personally delivered the training, quality suffered. By 2006, they shut it down and focused everything on IT services.

The first million dollars (₹4 crores back then) in revenue came in 2008. By 2015, the company had managed to hit ₹43 crores.

InfoBeans went public in 2017.

“We raised 37 crores, but we already had 33 crores in the bank,” Siddharth explains.

“So post-IPO, we had ₹70 crores. The whole idea was to invest in growth—organic and inorganic.”

After the IPO, InfoBeans expanded from the US to two new geographies: Germany and the Middle East. They also started building capabilities in ServiceNow and Robotic Process Automation.

The company is on track to cross the ₹500 crores mark in FY26.

One thing that defined InfoBeans from early on was their approach to team member ownership. The founders had been following Infosys closely, and one thing impressed them: before going public, Infosys gave out stock options to its people.

“We’ve been following Infosys quite closely,” Mitesh explains.

“One of the things that inspired us quite a bit was that, before going IPO, they actually ended up giving out stock options to people. We did the same.”

The question now became: how do they go from ₹400 crores to ₹4,000 crores?

Path to ₹4,000 crores

The strategy that would define their next phase is already clear: use platform technologies as a wedge to enter large enterprises, then expand through custom development.

“Newer technologies are client acquisition engines,” Siddharth explains.

“Even today, when you look at ServiceNow, Salesforce—we have a platform which allows us to go inside the larger organizations. The bulk of the business comes when we custom-develop products with these organizations.”

An iPhone app might be small, short-lived, and limited in scope. But InfoBeans used it as an entry point.

“We got a client through an iPhone app development project, back when iOS was still in beta testing mode, and that client is still with us. We ended up doing about a million dollars every year with them in the last 10 years of our 15-year-relationship.”

The involvement of Phaneesh Murthy as advisor has brought a new layer of rigor to how InfoBeans thinks about market opportunity. Rather than thinking about the Target Addressable Market (TAM) in aggregate, he introduced a different framework: the TAM per customer.

“What is your addressable market? Every startup looks at the addressable market,” Mitesh explains.

“Phaneesh told us, why are you looking at the addressable market in aggregate? At the end of the day, you will be working with a customer. A team is going to work with a customer. That team’s job should be to look at the TAM that the customer has to offer.”

“When you’re going out there and looking at account expansion, the job of the account manager is to expand the TAM. Everything else will take care of itself.”

The math becomes tangible: if a VP has a five-million-dollar budget, you either need 20 such VPs to get to a hundred-million-dollar TAM, or you need to go to that VP’s boss, who might have a $50 million budget. Then you look at working with two such bosses instead.

“That’s how you grow your account penetration and reach,” Mitesh says.

“His anecdotes, directly from the horse’s mouth: from $2 million to $700 million in 10 years. And then after that, iGate was another massive success story with a billion-dollar Patni acquisition.”

In 2019, InfoBeans made its first US acquisition: Philosophie Group Inc., a design engineering company based in Los Angeles, which had clients such as Google.

The logic was simple—Philosophie did the early validation work (user research, prototyping, testing), then recommended clients for full-scale development. InfoBeans handled the development. The top of the funnel fed the bottom.

In 2021, they acquired Eternus Solutions, a Pune-based Salesforce platinum consulting partner, in an all-cash deal. This expanded their Salesforce capabilities from about 100 people to a much larger practice of about 400 people.

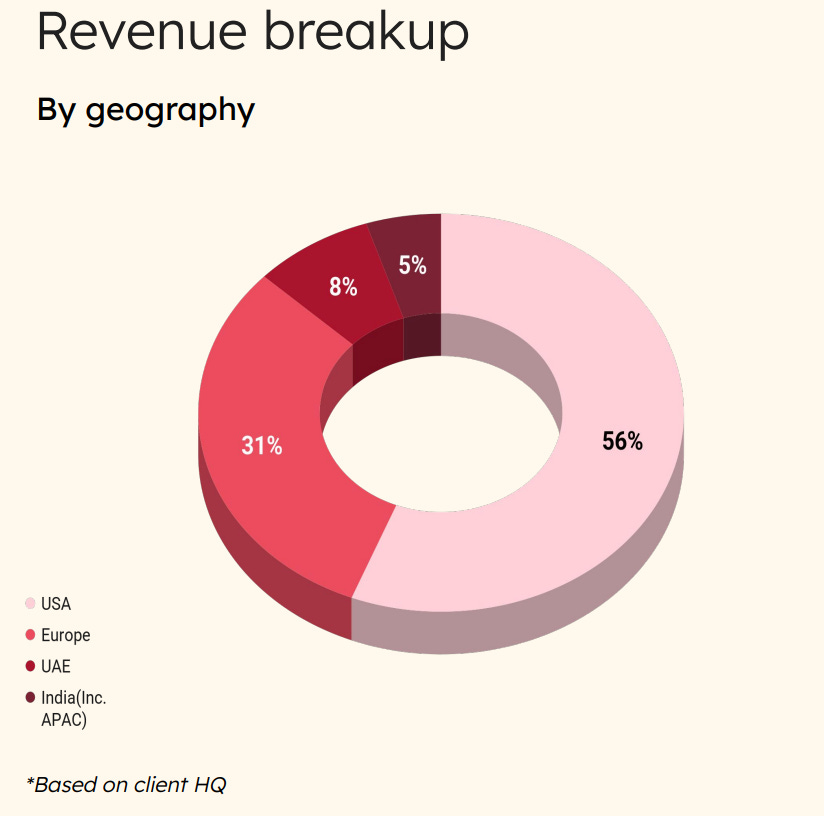

Today, InfoBeans has over 1,500 employees serving 42 large enterprise clients (among the 80-odd in total) across the US (56% of revenue), Europe (31%), the UAE (8%), and India (5%). They are a Microsoft Gold Partner, Salesforce Summit Partner, and ServiceNow Premier Partner.

These numbers tell the story:

“80% of our revenue was coming from the top 10 customers when we went public. Now we have diversified—55% comes from the top 10.”

Geographic Strategy

InfoBeans’ geographic strategy is more nuanced than simple market expansion. Each region has developed its own character based on the industries and services that naturally evolved there.

“If you were to really bifurcate our three big offerings in three big geographies,” Siddharth explains.

“The Middle East is a lot of Salesforce. Europe is a lot of ServiceNow.And US is a lot of core engineering work, though ServiceNow has definitely been growing pretty rapidly here in the US as well.”

The Middle East book is heavily weighted toward real estate clients; companies like Emaar. It wasn’t planned; it just happened naturally, given Dubai’s economy.

“You take aside the brick and mortar work, the customer interaction part is largely marketing-driven, sales-driven. Therefore, you see a lot of Sales Cloud implementation, Marketing Cloud implementation on the Salesforce side.”

The company has developed a methodical framework for identifying ideal clients. Tech companies in the $250 million to $1 billion revenue range have enough tech spend to become a large customer potential. For manufacturing in Europe, the minimum bar starts at $1 billion. Life sciences and real estate follow similar one-to-five or one-to-ten billion dollar customer profiles.

“The most interesting part to us was looking at a lower segment on the tech company side because their spend is significantly higher on tech,” Siddharth notes.

“They’ll probably spend roughly 40 to 50 percent of that money. And that’s your $100 million TAM client.”

The Competitive Landscape

InfoBeans operates in one of the most competitive industries on the planet: IT services.

The Indian IT services industry is dominated by giants—TCS, Infosys, Wipro, HCL Tech—companies with revenues in the tens of billions of dollars, hundreds of thousands of employees, and decades of institutional relationships with Fortune 500 clients.

So how does a company from Indore compete?

“We always focused on building relationships with large companies, project-based work, no body shopping, no sub-contracting business,” Avinash says.

“Value-added work is where we want to build our business with our clients.”

The wedge strategy has proven remarkably effective.

ServiceNow and Salesforce aren’t just technologies—they’re Trojan horses that get InfoBeans inside enterprise accounts. Once inside, the expansion happens through custom development, integration, and ongoing support.

“If with one customer I’m only doing ServiceNow. Can I do Salesforce there? Can I do AI there? Can I do automation?”

Currently, the ServiceNow practice has about 300+ employees and is growing fastest. Salesforce has about 400 people. Together, these platform businesses represent the entry points for most new enterprise relationships.

But the real differentiation isn’t technology—it’s something harder to replicate.

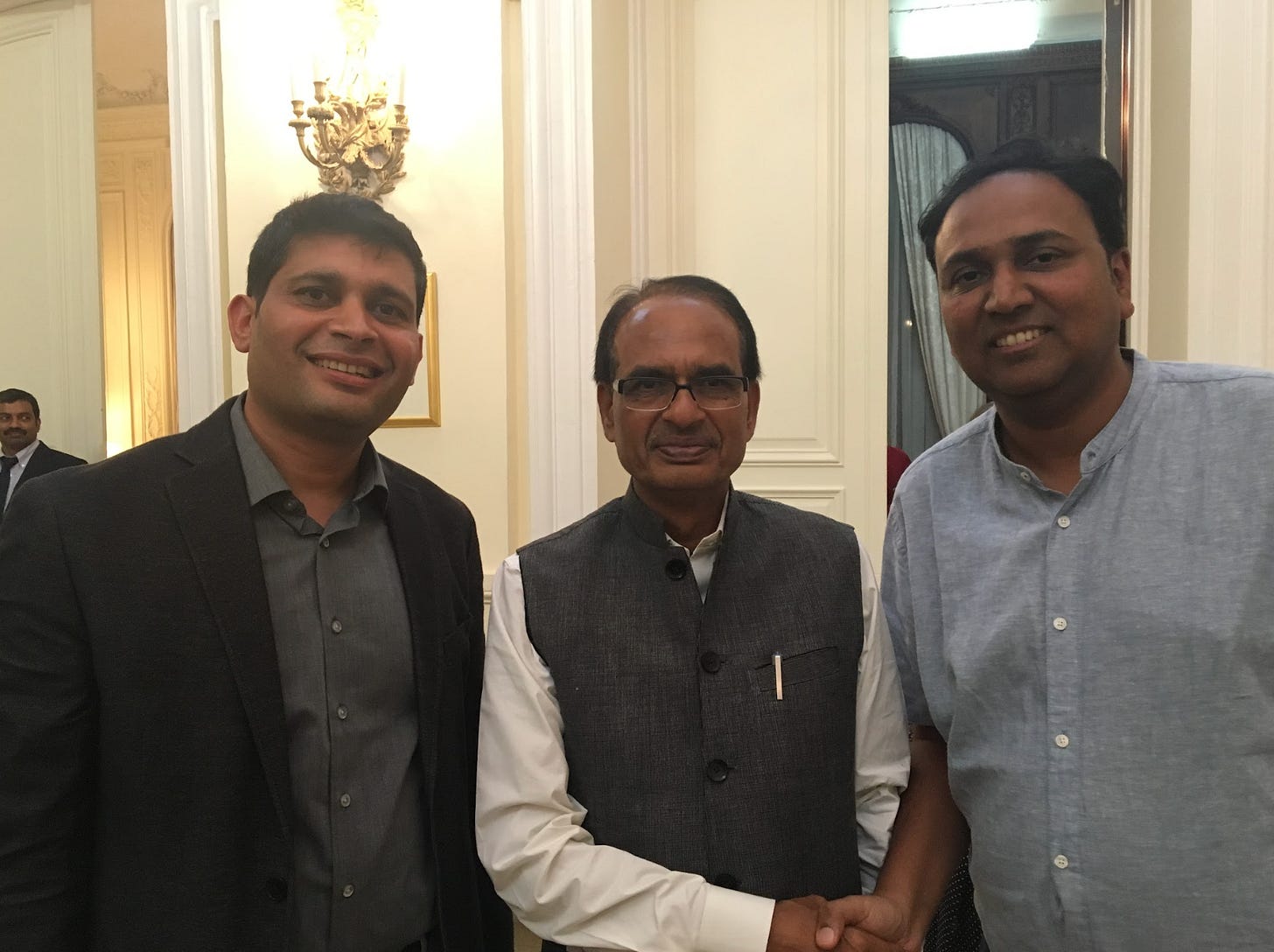

“The differentiation for us till date is the fact that humans do business with humans,” Mitesh says.

“That requires sitting in front of them, seeing them in the eye, and shaking hands with them. And whatever you can provide at that point in time, what kind of credibility you can generate, and then back it up with whatever you deliver.”

The pattern is consistent across successful accounts: trust compounds over time.

“It might sound like a cliché, but trust is the only differentiator that sustains. Price, you can always find somebody cheaper. Skills, you can always find somebody smarter. And you need all of that, by the way. There’s a baseline plus a lot more that you have to bring to the table.”

“But when the question becomes of competition, competition will potentially put in similar type of expertise. Bigger companies might actually have a whole showcase of things to show them. What they don’t carry is the attitude. What they don’t carry is the passion to deliver.”

Mitesh distills the input to generating trust into one word: attitude.

“When things go wrong, standing right next to them, trying to figure out what went wrong and how we can prevent it from happening — that’s solidarity. Doesn’t matter whose fault it is.”

“A lot of times, these problems and challenges come from many different corners. And they come to us and say, ‘Thank you for helping us out. This wasn’t even your problem.’ That’s a virtuous cycle of trust that you’re constantly building.”

This explains one of InfoBeans’ most unusual investments: their world-class office facility in Indore’s Special Economic Zone, and the upcoming IT park they’re building.

“A lot of people who visit the current facility, which is actually a world-class facility are really happy,” Siddharth explains.

“We’ve seen that they start to give you more work. A physical visit to the Indore office increases our business size and, wallet size of that client.”

The new IT park is even more ambitious. Built on government land, it will serve as InfoBeans’ campus while leasing excess space to other companies.

“The government said, ‘Why don’t you build your own campus and give the remaining space to people for lease? If you create an ecosystem, it will bring more multinational companies to the city.’”

“It’s a long-term call option for us to grow inorganically as well. If we incrementally grow, we can always recover those spaces anyway.”

The competitors InfoBeans faces aren’t the Tier-1 giants—those companies operate at a different scale with different client expectations. InfoBeans competes with mid-tier players like Happiest Minds, Persistent Systems, and Globant, as well as specialized boutiques in specific technology domains.

Their edge? Longevity of relationships (9+ years on average), depth of domain expertise in specific verticals like insurance, and the ability to move fast without the bureaucracy of larger organizations.

Margin Protection Through Value Creation

The approach to margins at InfoBeans is fundamentally different from the commodity mindset that dominates much of IT services.

“One of the things we are constantly thinking of is how we can create additional value on which a premium can be commanded?” Mitesh explains.

“Because when you are in a rat race of hourly rates, then you are a commodity.”

A banking client provides a concrete example. Procurement keeps coming back asking why InfoBeans charges $40 an hour when others quote $30. The conversation continues about value delivery.

Recently, InfoBeans went to this bank’s CIO with an unsolicited demonstration of how they could utilize AI and automation together to improve outcomes. The client hadn’t asked for it.

“The CIO was so happy and so impressed. He made us meet 10 of his direct reports, made us do 10 different demos to each one of them, and said, ‘Whenever the bank is ready to take on AI, because a lot of banks are actually still not open to AI, you will be the ones we will be asking for.’”

That CIO is the one who protects the premium pricing from procurement pressure.

“He’s the guy who’s been helping us keep procurement at bay. He’s the guy who’s saying this is a premium provider. Don’t go after them.”

The AI Market Opportunity

Avinash points out an exciting prospect for InfoBeans:

“We see AI as a big opportunity. IT firms that were merely focused on bodyshopping are going to struggle at their already large scale because the goalpost has shifted—AI will almost certainly commoditize tasks such as writing code—this shifts the value towards designing solutions which unlock revenue or reduce costs for clients. This is where we come in.”

The pattern is familiar—it’s the same wedge strategy, now applied to AI. Get in with an AI proof-of-concept, expand through implementation and integration.

“People have to upgrade their abilities via AI and focus on delivering solutions to customer problems,” Avinash points out.

“Those who cannot use AI tools and focus on designing solutions will be left behind. Whether you increase your headcount or not, the quality of people needs to improve.”

InfoBeans has a dedicated team focused on AI, including their proprietary accelerator called Expona. In 2025, the company achieved CMMI Level 5 certification and launched multiple generative AI initiatives.

“Every customer is looking forward to AI. They are so excited about it. They want to do it. Quite a few of them try to do it themselves.”

“We continue to build those prototypes at our end. At some point, they are looking at us because they don’t have enough capability.”

“Whatever capability you build, if you don’t have a customer, it’s going to die. It needs to fuel its own growth.”

Siddharth invokes Jevons Paradox—the observation that when technological progress increases the efficiency of resource use, overall consumption of that resource actually increases rather than decreases.

“Every time such a major revolution happens, like what we are seeing in terms of AI, there was a lot of apprehension. But when has the work stopped or reduced? It actually has grown. Since calculators came, since computers came, since the internet came. And now AI.”

The practical reality is more nuanced than apocalyptic predictions suggest. Siddharth recounts a recent lunch meeting with someone doing extensive AI work.

“His point is roughly about 30 to 40 percent of the skeleton gets put together in a very rapid fashion, for which whatever number of engineering talent you need to carry, you may not need that. But from that 40 percent to 100 percent journey, you can’t do it with AI. At least not now or for the next year or two years.”

“Because the nuances and the context of the business are so deep and so complex that if you were to do this with AI, you’re going to burn through whatever tokens you have available or you’re going to have such a high bill that a human might actually be cheaper than AI.”

Companies are already discovering this reality. They’re limiting AI usage for developers because token costs are spiraling.

“Suddenly, if you have such a massive AI cost running, at some point you would start to question how much of it is worth it.”

The Leadership Transformation

In the last 18-20 months, InfoBeans has undergone significant maturing at the leadership, advisory, and operational levels.

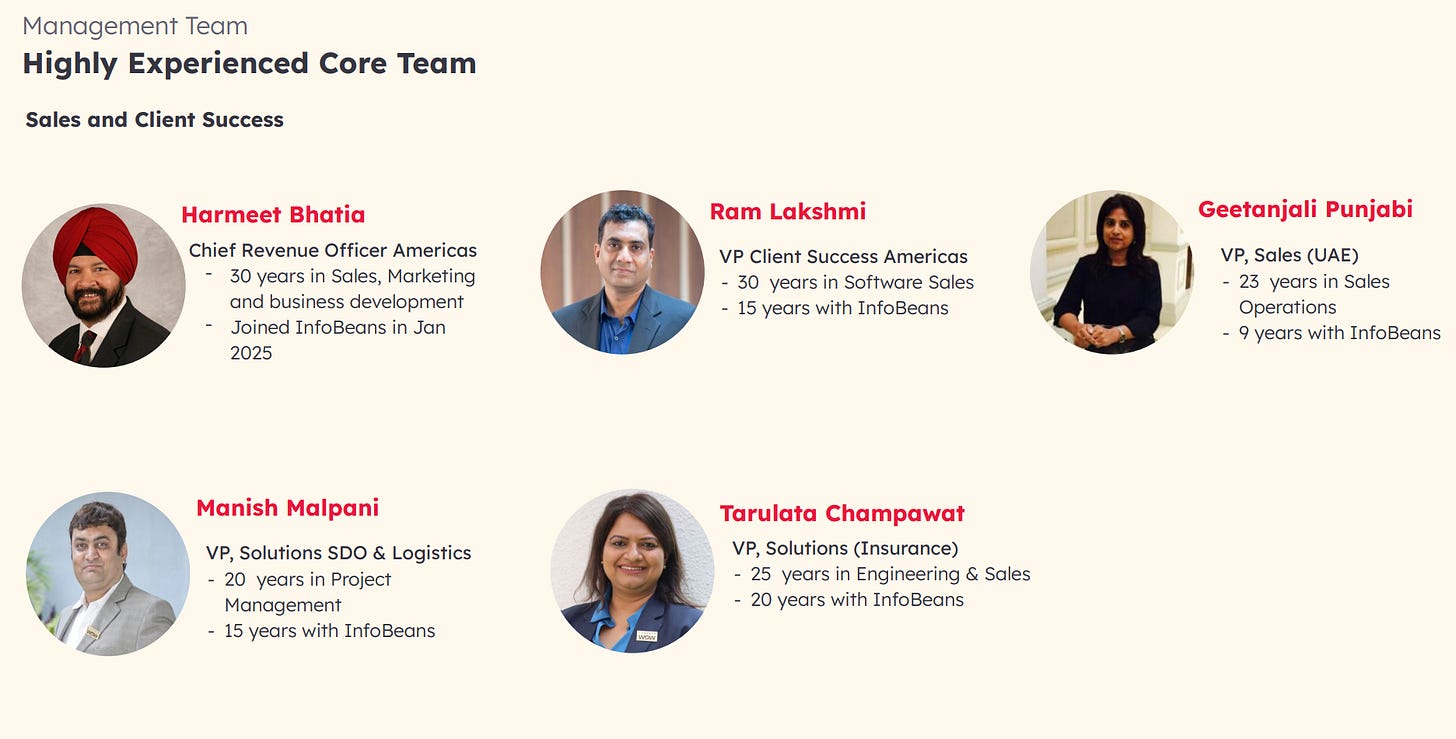

Harmeet Bhatia joined as Chief Revenue Officer for the Americas in January 2025, bringing 30 years of experience in sales and marketing. Phaneesh Murthy, the legendary former Infosys executive, joined as an advisor to the Board in June 2024. Opal Perry, Chief Data & Technology Officer at easyJet, joined as an Independent Director.

The operational restructuring is equally significant. Previously, salespeople were specialized—a ServiceNow person would sell only ServiceNow. Now, each customer success person is assigned three top clients and is expected to know everything InfoBeans offers.

“Salespersons should know everything. So that restructuring is happening on the client side right now.”

“We are clearly moving in that direction. We’re making every effort. We’re leaving no stone unturned.”

There’s also a new focus on acquiring clients rather than just growing existing accounts.

“Our pace of getting new clients was much lower. We were mostly reliant on repeat business from our existing clients until a couple of years ago. But we realized that something needs to be done aggressively.”

The target: 20% organic growth in new client acquisition annually.

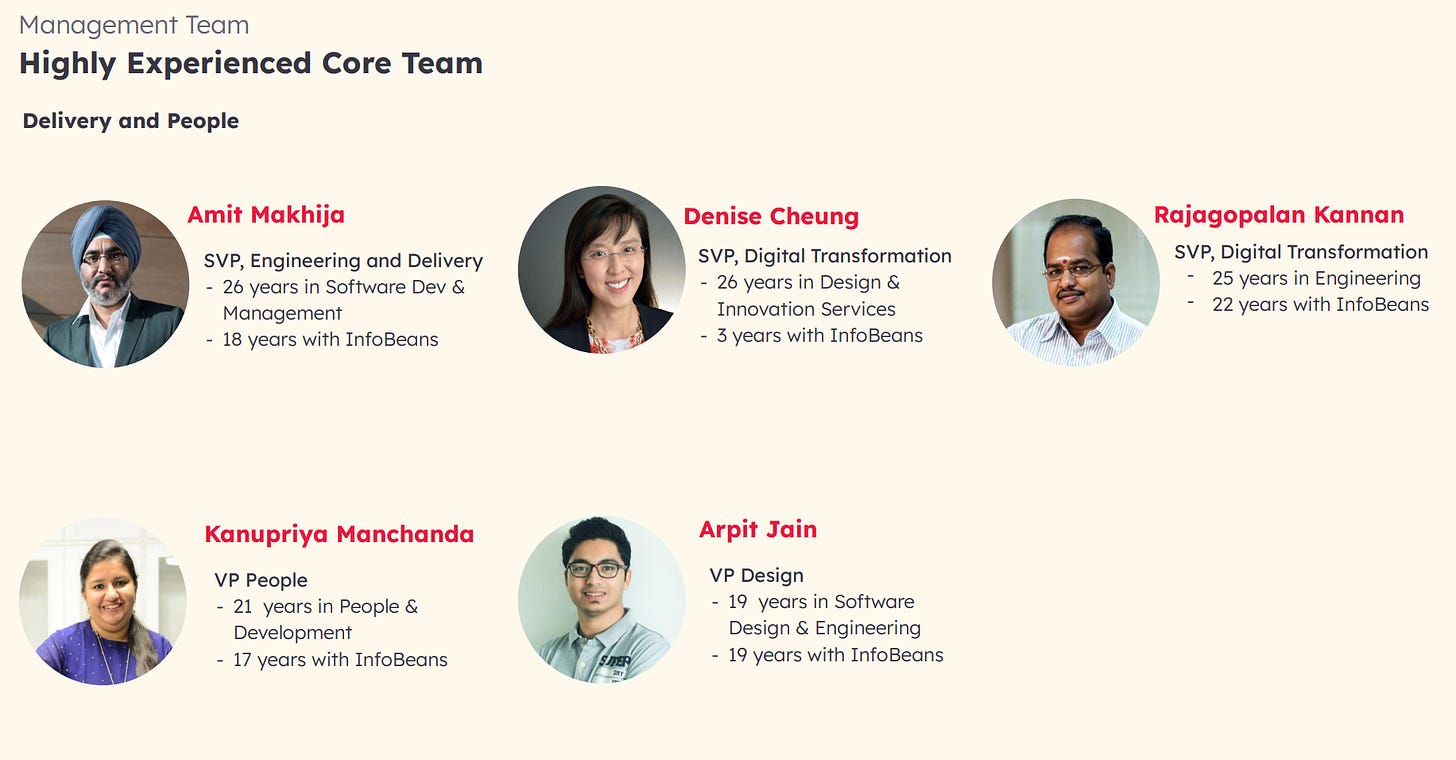

The approach to leadership development at InfoBeans is distinctive. Rather than importing talent from larger organizations, the company has found more success with homegrown leaders.

“Our efforts to bring in outside knowledge actually failed,” Mitesh admits candidly.

“Majority, I would say, is homegrown. And that largely comes from people who continue to stay with us, continue to carry that sense of ownership, and continue to develop and build that program.”

The mandate for every leader is simple but powerful: find your own replacement.

“That’s the only way you’re going to grow. If somebody else cannot do your job, you will be stuck in that job. And that resonated, at least with a lot of leaders who chose to stay, who chose to grow.”

The philosophy extends to how people identify with the organization. Mitesh explains a framework from their 2022 leadership retreat:

“Either you are working for InfoBeans, or you are working with InfoBeans, or InfoBeans is your company, or you say, ‘I am InfoBeans.’”

Each level means something different. Working “for” InfoBeans is a job. Working “with” InfoBeans is a partnership. But “I am InfoBeans” comes out when someone’s personal reputation becomes bound to everything that gets done at InfoBeans.

“If somebody works as if ‘I’m working for InfoBeans,’ they are in a job. Everybody has a place. All four categories have a place in the company. But the longevity gradient is actually exponential as you go towards ‘I am InfoBeans.’”

The Micro P&L Structure

One of the more distinctive operational innovations at InfoBeans is how it pushes P&L ownership deep into the organization.

“At different levels of leadership—take an engineering director who’s in charge of delivery for a client—every single project in that client’s purview will be looked at as a P&L,” Siddharth explains.

“That P&L will be managed by the individual project managers or the leaders who are running the show on the projects.”

All of that rolls up to the engineering director as a client P&L. The structure is deliberately simplified: revenue (billing), direct cost, gross margins. No complex overhead allocations or ambiguous cost centers.

“Every engineering director and their subsequent leaders have gross margin targets. And these gross margin targets are tied to incentive compensation, above and beyond what they get on their base pay.”

The result: leaders at multiple levels are making real tradeoffs between preserving gross margin and investing for future growth. These aren’t theoretical exercises—they’re daily operational decisions with personal compensation implications.

“This is not namesake leadership at that level,” Mitesh notes.

“These are tough problems to solve.”

The company also sponsors management education for promising leaders—four have attended IIM Indore’s executive programs, with others at different institutions. The investment in human capital is systematic, not episodic.

After 25 years of building the company hands-on, the three founders are now focused on guidance rather than getting into execution themselves.

“I think what we realized is that we need self-starters. We need people who can drive. Even if they make mistakes, that’s okay. We don’t want people who are followers.”

Saying No

The commitment to values isn’t just rhetoric. InfoBeans has walked away from potentially lucrative opportunities when they conflicted with company principles.

“We were approached by a gun manufacturer to do work for them,” Mitesh reveals.

“We point-blank said no. Imagine the amount of money they carry and the kind of projects inside. This could have been a massive account for us, but we didn’t take it. We walked away.”

The philosophy Mitesh articulates for his team captures the ethos:

“Don’t try to win, just win them over. Do you want to win or do you want to win hearts?”

For InfoBeans, winning is an outcome. Winning hearts is the method.

The three founders also live by a different standard than might be expected of entrepreneurs who’ve built a company approaching ₹2,000 crores in market cap.

“We live a very normal type of lifestyle,” Mitesh says.

“I wouldn’t say frugal, but nothing outlandish, nothing fancy. Because we realize at the end of the day, what good is money if you can’t put it to good use?”

Metrics

Enterprise clients (₹1 crore+ annually): 80

The top 20 clients generate 70% of revenue

Average large enterprise relationship duration: 9+ years

Repeat business: 95%

Geographic Distribution:

USA: 56%

Europe: 31%

UAE: 8%

India/APAC: 5%

Business Mix:

InfoBeans Digital Transformation: 60%

InfoBeans Salesforce/ServiceNow practice: 40%

Stock Performance

The stock has delivered approximately 44.7% returns over the last 12 months, significantly outperforming both the broader market and many IT sector peers. Over 3 years, the return stands at around 14.8%.

The company has completed two buybacks—in 2021 and 2025—demonstrating confidence in the stock and commitment to returning value to shareholders.

Notably, the founders never participated in the buybacks; instead, they themselves bought back approximately 3.5 lakh shares from the market.

The founders point out:

“Since the IPO, we (founders) never sold any shares. We have always bought back historically. We intend to sell 3% between the three of us in the near future to fund a few personal expenses for our families. Other than that, we are not planning to dilute any more stake from our holdings.”

“The idea is we wanted to be transparent about it. I actually asked around, but it seems India doesn’t have anything like the calendar that US companies publish ahead of the year. But being transparent is a good idea. It doesn’t hurt.”

The Vision

The direction is clear. InfoBeans wants to hit ₹4,000 crores by around 2033. The investments in leadership, AI capabilities, new geographies, and the IT park are all aligned toward this trajectory.

Avinash says, “Before we hang our boots, we want InfoBeans to at least get to the next level. And that next level, which will keep us happy, would be the 10x level.”

For the founders, the path from $50 million to $500 million requires maintaining the fundamentals while upgrading the systems. Siddharth concludes:

“We still think at the very core of this, you would still need people who carry this burning desire in their heart to do good, to do something which creates long-term value, to do something that is meaningful.”

“Once we get to the half a billion revenue mark, we may look like a different company, we may look like a more mature company. But it is truly my hope that at the very foundation of it, that same burning desire to create long-term value remains.”

What makes InfoBeans different from the hundreds of IT services companies?

Perhaps it’s the discipline of reinvesting profits instead of taking money out of the system. Perhaps it’s the Jain philosophy of simple living that they grew up with—frugality not as a strategy but as a way of life.

Or perhaps it’s something more fundamental: the understanding that in a business built on trust, the most valuable asset is time.

Thirty-seven years. Three friends. One company. InfoBeans.

Safe Harbor Statement: This article contains forward-looking statements that involve risks and uncertainties. Actual results may differ materially from those projected.

This article was prepared based on interviews conducted with the founders of InfoBeans Technologies Limited. This is NOT a paid article.

If you want to discuss an opportunity with InfoBeans Technologies Limited, please reach out to us at banjan@tal64.com.

This beautifully reinforces what many investors overlook: the value of studying a company’s past decisions & DNA arc. I believe this tells us far more about the durability of a business than any forward model can. Superbly research.