The Cantabil Story

How Vijay Bansal built a Rs 2500 crore retail fashion brand starting from a small general store in Haryana—a masterclass on learning value addition, and the power of never giving up.

The eye-opening aspect of Vijay Bansal’s experience of learning the retail business is how to construct a profitable value proposition.

"The path to profit in India involves identifying your aspirational customer because that’s where a gap exists between your costs and the price the customer pays. You need to position yourself within that zone."

"In India, the purchasing power is still limited. We wanted to make a brand for the aspirational segment."

FY2025 Performance:

Revenue: ₹721.1 crores (17% growth Y-o-Y)

EBITDA: ₹205 crores (26% growth Y-o-Y)

Net Profit: ₹74.8 crores (20% growth Y-o-Y)

Stores: 600+ across 289 cities in 20 states

Retail Space: 7.85 lakh+ square feet

Employees: 5,000+

This is the extraordinary story of Cantabil—a company that survived a 90% stock price crash, emerged debt-free, and continues to grow at 20% annually. But more than a business success story, this is a testament to how traditional values of hard work, honesty, and smart execution can build lasting enterprises in modern India.

It is also a testament to the razor-sharp mind that Vijay is blessed with.

A kirana store

"I belong to Jind, Haryana," Vijay Bansal begins.

"I would come home from school, put my school bag aside, and then go to the shop. I worked there for an hour or two, then come back home. During festivals, I had to spend more time there. This is how I learned."

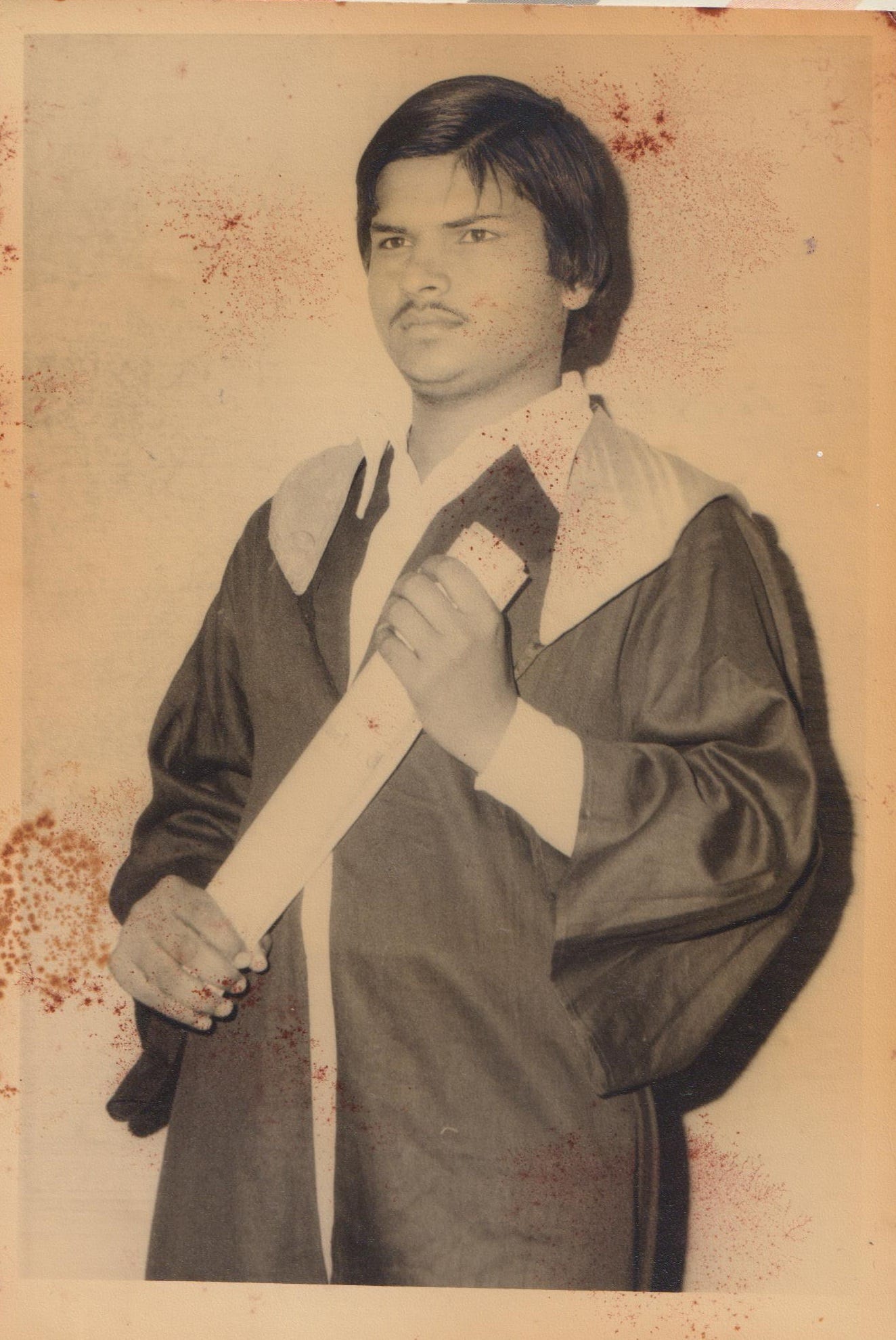

After completing his B.Com in 1979, Vijay naturally gravitated toward the family business. The family shop was a typical general store in a small district.

"After graduation, naturally, I knew that I had to work in our family shop."

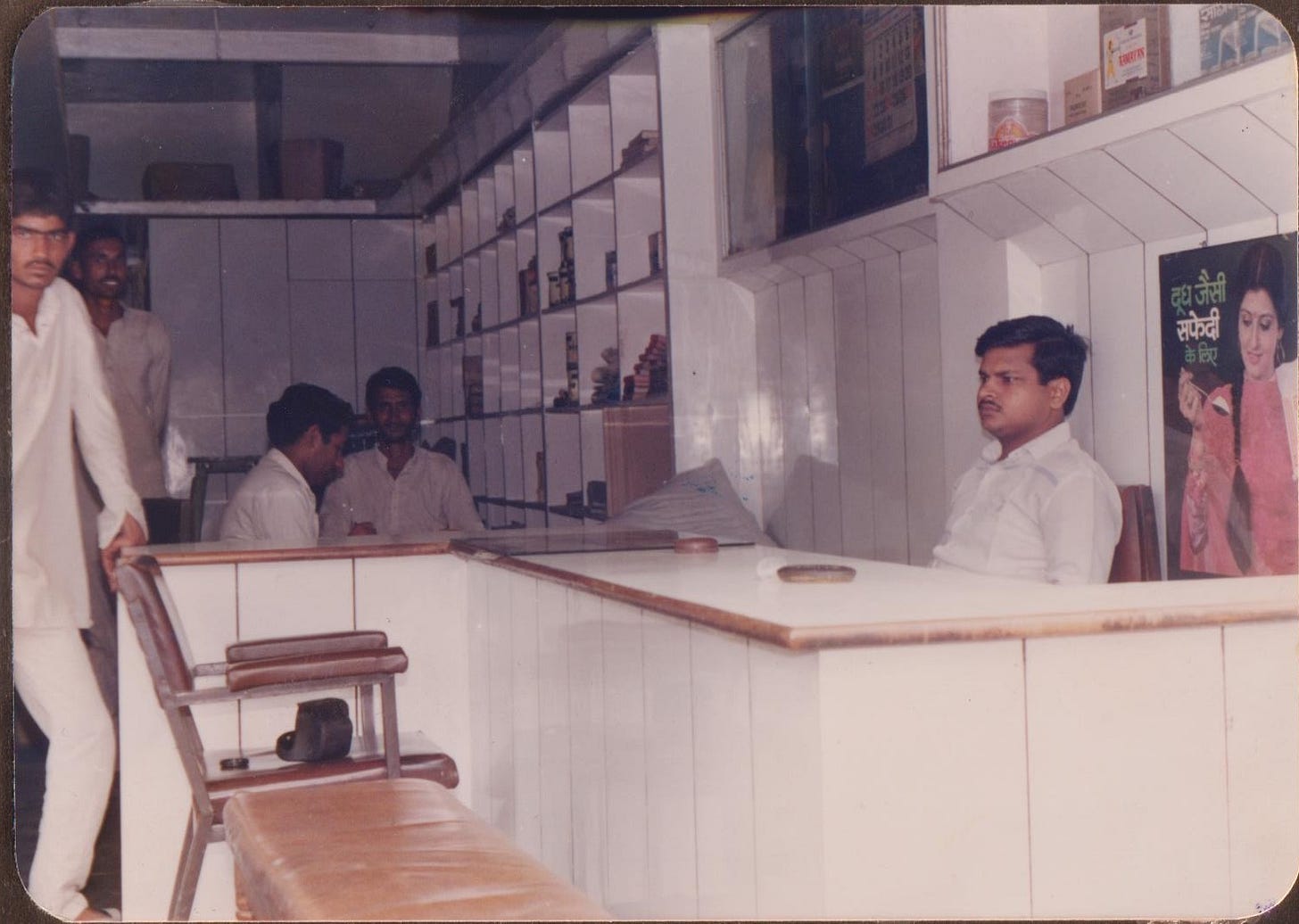

"Jind was not a village—it was a district in Haryana, a small district with a population of one lakh or so at the time. The shop itself was around 700-800 square feet, selling dal, sugar, soap, etc."

But young Vijay had bigger dreams.

"When a person finishes education and becomes young, he sees new dreams. My father made a small workspace for me and told me to work from there. Then I started working on accounts and learned accounting."

Moving up the value chain

What happened next would shape Vijay's entire business philosophy. His approach was methodical and aggressive.

"Gradually, I became interested in agencies and business. Because of our products, I got interested in distribution."

"My entrepreneurial journey began with securing the distribution rights for Haryana Dairy Development. This was soon followed by associations with the National Tobacco Company, Tarzan Bidi, Dalmia Biscuits, Colgate, Amul, and Nirma. Each successive venture deepened my engagement with the distribution ecosystem and gradually nurtured a strong interest in building scalable business operations."

Vijay's growth strategy was simple but relentless.

"I proactively reached out to companies every day, expressing our intent to take on distributorship opportunities in untapped markets," he recalls.

"As our performance began to speak for itself, our ambitions expanded—we saw potential in marketing-led growth. That’s when we pivoted to intensive, city-wide door-to-door retailing, operating tirelessly from 10 AM to 9 PM, determined to build a deeper consumer connect."

This hands-on experience became his business education.

"While doing retailing with these companies, I learned marketing through practical experience. We worked with big companies—Colgate, National Tobacco, Amul, Nirma, Nippo Batteries, Stepan Chemical. We had distribution agencies for 30-40 companies. While working with them, I gained such valuable experience—I don’t think an MBA can teach you that."

Learning vertical integration

The transition from distribution to manufacturing came through relationships built in the agency business. A friend from Dalmia Biscuits suggested that Vijay start manufacturing biscuits.

In 1981, Vijay and his partners acquired one acre of land and applied for financing. But when Haryana Finance Corporation's inspectors arrived, they delivered sobering advice:

"The biscuit factories in Haryana are many. There will be intense competition. We don't recommend setting up a biscuit factory."

Vijay took that as a cue and began to search for other ideas.

"My brother-in-law, our partner, told us to start a cottonseed oil manufacturing business. He had a relative in Yamuna Nagar who knew the business. I decided to take his help and get into it."

The initial venture was a disaster.

"We suffered losses. My father told me to stop the factory. He said, ‘We could pay the loan EMI from our shop income. The shop income was good, and the work was stable. You should stop the factory operations.’"

They shuttered the operation, but Vijay saw an opportunity in seasonal demand a few months later as winter arrived.

"After 4-6 months, winter came. Mustard oil demand comes in winter. We got an idea to try once again. Instead of cottonseed, we manufactured mustard oil in the factory."

"Within that winter, we got a profit of ₹1 lakh in 2-3 months, and this is in 1981."

The results were dramatic.. This was 1981—Rs 1 lakh would be worth Rs 21.5 lakhs today (inflation-adjusted).

Success led to expansion and vertical integration. Vijay started understanding the compounding that occurs via value addition.

"I started learning the method of value addition and moving further up the value chain. We started trading oil. People used to buy oil in drums. We had large storage tanks for oil. Using big tankers with 15,000 kg capacity, we started selling to oil mills and refineries. So we started with oil manufacturing, and now we were into oil trading as well."

Having a business-oriented family certainly helped.

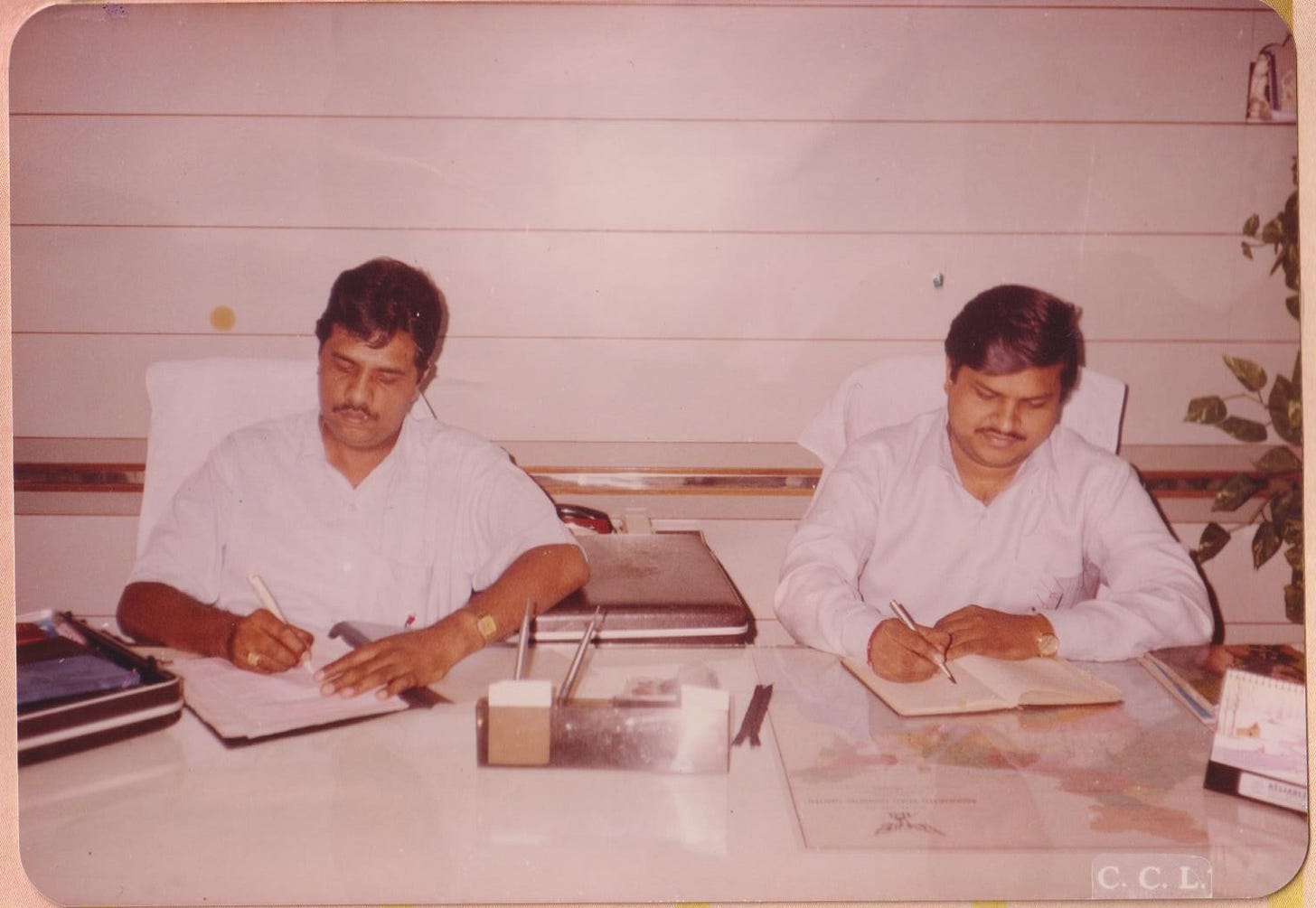

"We were two brothers. My elder brother, Suresh Bansal, used to look after the oil business more. I used to look after the distribution agency and retailing business more."

Building partnerships

In 1986, another opportunity emerged.

"My brother's friend, Chaudhary, already had a Liberty Agency in Jind. He was in touch with the company. He proposed the Delhi opportunity to the company—at Connaught Place."

The investment was significant.

"He said there would be an investment of ₹2 lakh. Our income was so good that ₹2 lakh was manageable. We thought that for ₹2 lakh, we could get a shoe shop in Connaught Place, which is a very prestigious location."

Vijay also thought partnering with someone who understands this business better made sense.

"We became partners with Chaudhary—we got 60%, he got 40%."

"I divided my 60% share as well — I gave 30% of our 60% to my brother-in-law. He had completed his MA and was available. I brought him to Delhi."

The showroom's financials were modest but stable.

"We didn’t earn very high income from that showroom, but it did provide me with a profit of about ₹1 lakh per year, while my brother-in-law also earned ₹1 lakh. During that time, we were able to rent a house, maintain a car, and manage our yearly expenses of around ₹1–2 lakh."

Zips and Buttons

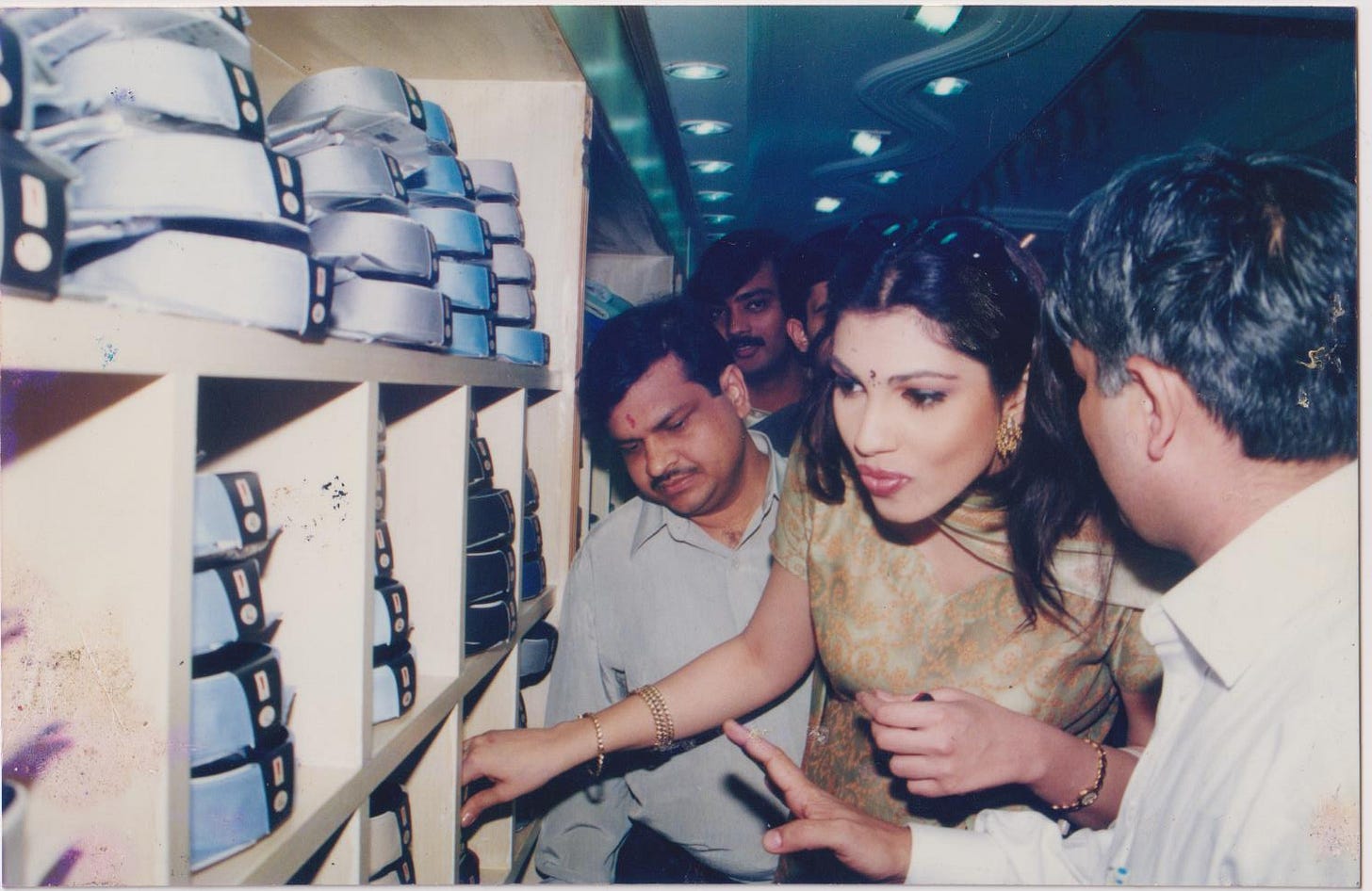

The entry into garment accessories came through a chance conversation.

"A relative of my brother-in-law had come from Kolkata. During our conversation, he said that the Jindals have started a factory making fasteners that are used in pants."

Intrigued, Vijay investigated. The meeting with the Jindal family was initially discouraging. The Jindals had good reason for skepticism.

"Mr. Shiv Ram Jindal, along with Mr. Ravindra Jindal, had started this factory. They called us for a meeting. We went to see them. I told them I wanted to become a distributor in Delhi.

They said, ‘You are a small business, not suitable for you. You won't be able to make it work.’"

"They had another distributor in Sadar Bazaar in Delhi who had a family business of selling zip buttons. They had a network. We were new here."

But Vijay's confidence from his distribution experience was unshakeable.

"I had confidence from my distribution agency experience that I could sell any product. I assured them I would pay money in advance. If we sell the product, fine. If we don't sell it, we won't return it. Even if we have to throw the product away, it won't be your responsibility."

His bold guarantee worked.

"He loved it. He said, ‘You don't have to give me any money in advance. I am making you a distributor’."

How to sell: Sell to the customer’s customer

"In our initial efforts to enter the garment accessories market, we began by approaching wholesalers in Sadar Bazar to sell zippers. We expanded our outreach to other leading wholesale hubs such as Ahmedabad, Surat, Mumbai, and Baroda."

"While the early response from wholesalers was tepid, these interactions provided valuable insights into market dynamics and helped us better understand the needs of the supply chain."

"Despite our persistent efforts, the business strategy failed to gain the expected momentum, and the venture ultimately did not succeed. This initial setback, though disheartening, offered critical lessons and deeper exposure to the operational intricacies of the industry."

Amid early setbacks, Vijay’s brother-in-law contemplated exiting the venture. But Vijay, drawing upon his prior experience in tobacco distribution, arrived at a pivotal insight.

"I recalled how, during my time with National Tobacco, we would introduce new cigarette brands by offering complimentary packets to pan shop owners. Once customers began purchasing them, the demand naturally compelled wholesalers to come on board,” he explains."

This reflection led to a strategic shift:

“I realized that in the case of zippers, the actual demand drivers were not wholesalers, but tailors—the true end users."

"So, instead of waiting for wholesalers to show interest, we decided to engage directly with tailors, allowing market demand to pull wholesalers into the supply chain organically."

The solution was elegantly simple.

"I provided a zip to a salesman, created a route plan for him, and directed him to approach the tailors. The zip was sold at ₹50 each, and by the end of the day, he had sold 10 pieces — earning a total of ₹500."

Success with one salesman led to immediate scaling.

"The next day, I made route plans for 5 other salesmen. First, I gave samples. Then they took zips to tailors and gave them zips and took cash payment."

The results were spectacular.

"With 10 salesmen each earning ₹500 from zip sales, I made ₹5,000 in one day. All the remaining zip inventory was cleared in one day. That's incredibly fast inventory turnover."

Vijay immediately expanded the model across cities by working with his family members.

"I also helped relatives who were in Jaipur, Lucknow, Bombay. I told them the same pattern. I told them to sell to tailors, and they succeeded."

"We had sales of ₹30,000 per day. The production of the company was not sufficient for us. Then we realized that the more volume we sell, the more profit we made. I used to sell for ₹30,000 per day. In a month, we earned ₹1.5-2 lakhs in profits."

When the Jindals introduced polyester buttons, Vijay promptly added them to his distribution portfolio.

"When the polyester button was introduced, it was sold as a Taiwanese product. In India, it used to be called the Urea button. Normally, the shirt button used to break. But the quality of polyester buttons is higher—they are also dyeable, look shiny, and don't break."

The same pattern repeated with the buttons business. Vijay's low-margin, high-volume strategy was deliberate.

"My theory was: once you generate volume, profit will automatically follow. Since we were new, we had to create volume first and establish our market presence."

By this time, Vijay had substantial profits from the zips and buttons business.

"I had zip business worth ₹2-3 lakhs in annual profits. I had a button business worth ₹3-4 lakhs in annual profits. In this way, I started earning a profit of ₹6-7 lakhs. In those days, the value of ₹6-7 lakhs was substantial." (Editor: It is worth approximately Rs 1.6 crores today)

More value addition to move further up the value chain

A friend's introduction led to his entry into garment retail.

"My friend's uncle told me he could get me a distributorship for TNG, which was a garment brand. He took me there. Initially, my conversation with Mr. Dwarka didn't go well. Two days later, he suddenly called me and said, 'Vijay, you are a very dynamic person. You should become a garment distributor in Delhi."

Vijay saw this as an opportunity to diversify while maintaining his core business. Working with TNG for several years gave him crucial insights into the garment retail business.

"I liked this business of garments. I thought that it had a good margin. At that time, we used to put MRP of 2.5-3 times the cost."

The birth of Cantabil

In the year 2000, Vijay secured a retail space in Delhi’s prominent Rajouri Garden locality, envisioning it as a premium outlet for TNG garments, for which he was already a distributor in the region. Wasting no time, he contacted the TNG & to his surprise, the brand declined his proposal, stating that the retail rights for that area would be granted to another party.

"I had entered into the lease with full conviction,” he recalls.

"When they declined permission to retail TNG products at the location, I respectfully conveyed that the store would open regardless, and I would find a way forward."

It was at that crossroads that inspiration struck.

Flipping through a dictionary one evening, he unexpectedly landed on an Italian page. A particular word caught his eye: Cantabile—meaning "suitable for singing."

"The word had a lyrical quality and a distinctly global resonance,” he reflects. "I felt it carried both elegance and universality."

With a slight modification—dropping the final 'e'—the name Cantabil was born, marking the beginning of what would soon become a pan-India fashion brand.

In the early days, the Rajouri Garden showroom showcased a curated mix of popular fashion labels such as Dash, Nadiya, Kairo, and Vans. Notably, there was no apparel bearing the name Cantabil.

"I began to question—why not create and retail garments under our own brand? We initiated the production of apparel under the Cantabil label and gradually phased out all third-party brands from the store. We made a deliberate decision to build our own identity—complete control over design, quality, and customer experience."

"By 2007-08, there were 300 Cantabil stores. We launched another brand called Lafenso and scaled this new brand to 200 stores. Together, the two brands accounted for a robust retail network of 500 stores and an impressive revenue of ₹200 crore. This growth trajectory culminated in a successful IPO, with shares priced at ₹135, raising ₹105 crore and establishing a market capitalization of approximately ₹210 crore."

When Everything Collapsed

The post-IPO honeymoon was short-lived and brutal.

"In 2012, retail in India started declining. Our share price started going down. It became ₹15 from ₹135. More than 90% fall. It was brutal."

The market conditions were devastating for mid-segment retail brands.

"In those days, no mid-segment companies survived. Like Lilliput, Cottons, Vishal, TNG—all retail brands were shut down."

"In 3 years, we had losses of ₹70 crores. In 2013, 2014, 2015."

Public perception was that the company would not survive.

"At that time, the whole world was thinking the company would close. Coming out of that and surviving the headwinds was a big challenge. At that time, our own people were saying that if the company were in the loss, then it would be destroyed. It would be closed."

Confidence

During the most financially challenging period of his entrepreneurial journey, Vijay chose transparency and accessibility over evasion—a rare trait in times of crisis, displaying grace under pressure.

“Those were difficult days,” he reflects.

“Cash flow was constrained, liabilities were mounting, and payment commitments were pending. The pressure was intense, and the phone calls relentless. Yet, I made it a point to answer every call. I listened patiently, acknowledged the concerns, and assured them of repayment. The conversations were honest, and that honesty often gave people reassurance.”

Unlike many who retreat into silence during such times, Vijay faced the situation head-on.

“If someone came to collect dues, I met them personally and communicated with clarity. I wanted to ensure that no one ever felt I had vanished or was avoiding responsibility.”

Even amid immense stress, his belief in the eventual turnaround remained unshaken.

“I had an inner conviction that I would steer the business back on track. I put my faith in persistent effort, and with divine grace, I emerged stronger.”

"We put the company in correction mode. We understood our mistakes and made the required corrections.. We enhanced product quality, enhanced the visual appeal of showrooms, stopped loss-making showrooms, and controlled discount strategies."

"We consolidated our stores and reduced them from 500 to 150—all Cantabil only stores."

Focus on Quality

The challenges of the downturn prompted a critical re-evaluation of Cantabil’s business philosophy.

"We learned an important lesson," Vijay reflects.

"In earlier phases, the business leaned heavily on aggressive discounting—product quality and brand positioning often took a back seat. But we came to realize that long-term value creation required us to build aspiration, not just affordability."

This shift in thinking coincided with a broader transformation in consumer behavior.

"The Indian middle class was evolving—becoming more discerning, ambitious, and style-conscious,” Vijay observed. “Tastes were maturing, and expectations around quality and design were rising steadily."

In response, Cantabil undertook a focused repositioning strategy. The brand prioritized product quality, refined its aesthetics, rationalized discounting, and optimized retail operations.

"We retained only profitable stores or brought them to breakeven. Visual merchandising was enhanced, and operational inefficiencies were systematically addressed. The result was encouraging—customers responded positively, and profitability returned."

This phase marked a new beginning—a strategic reboot that laid the foundation for sustained growth.

"Gradually," Vijay says, "the business stabilized, and momentum returned."

The financial turnaround was remarkable.

"For the past 7 years, my growth is 20% CAGR. In March 2021, we became 100% debt-free."

"This year (FY24-25), our sales is ₹720+ crores. Last year it was ₹616 crores. Last year our profit was ₹63 crores. This year our profit is ₹75 crores."

"Net profit is approximately 11%. EBITDA is 28%."

Product-Channel Fit

Cantabil has shrewdly chosen to focus on owning the customer experience and customer service part of the value chain. Vijay lists some numbers out:

"Right now, we have 600 stores. Approximately 50% customers are repeat customers, 50% are new customers. About 1.5 lakh bills per month across all stores—this translates to daily sales of ₹2 crores approximately at the moment."

"35% is the retailing cost—rent, salary, electricity, all together plus GST. My gross profit is 57%."

"We have no debt, no debtors. Cash is deposited from each store the next day, or at least in the same week. I have only inventory where our cash is invested for working capital."

"22-23% of stores of the 600 stores are franchises. The rest are company-owned stores. For us, considering our market and our experiences so far, I believe having a very good control over the customer experience and service quality via our own stores makes a lot more sense."

Cantabil's retail model has inherent cash flow advantages that Vijay leverages effectively.

The franchise model is tightly controlled.

"Even if I have a franchise, the stock they have is on consignment. The stock is mine. I have taken security from them. The amount that was sold today will be deposited in the bank the next day."

Digital sales are growing.

"This year, digital will be ₹45 crores out of ₹720+ crores. Last year it was ₹34 crores. 50% is on Myntra, then Flipkart, Amazon, and our own site."

However, Vijay is wary of over-relying on online marketplace economics.

"These sites are taking such a big commission that online is becoming more expensive than offline. If I add their commission and returns, it comes to 37%. Offline is 35%. So there's no advantage really, and in comparison, I get to engage my customer better offline and deliver excellent service which builds brand equity."

Operational Metrics

Average Basket Value: ₹4,014

Average Selling Price: ₹1,051

Same Store Sales Growth: 3.97% (FY25)

Customer Repeat Rate: ~50%

Online Sales: 6.2% of total revenue, targeting 8-10%

Position in the Market <> Profit Pools

The eye-opening aspect of Vijay Bansal’s experience of learning the retail business is the following insight that he shared about how to construct a profitable value proposition.

"The path to profit in India involves identifying your aspirational customer because that’s where a gap exists between your costs and the price the customer pays. You need to position yourself within that zone."

"We wanted to make a brand for the aspirational segment. My initial stores opened in premium markets like Connaught Place, Greater Kailash, South Ex, Ajmal Khan, and Rajouri Garden. We launched the brand in the top 5 markets of Delhi. We made products according to that customer base."

Cantabil positions itself carefully in the mid-premium segment.

"We right in the middle. In the segment below us, the basic average price is ₹400-500—this is standard offering in Tier-2 and Tier-3. Our average price is ₹1,100-1,200—this price point is aspirational for Tier-2 and Tier-3. Premium is ₹1,800-2,000, which is aspirational for Tier-1 and to some extent Tier-2 (where they are not always available). And then you have the non-Indian owned brands of the world above, which is aspirational for Tier-1."

On the other side of the story is the costing aspect of it, especially the rental cost for the store.

"Around 50% of turnover comes from Tier 3 cities, while around 40% of our sales are from Tier-2 cities. We focus on this with intent. Tier 2 and 3 are good—rent is reasonable/low, and the youth is aspirational and is moving toward brands."

The spread between the price an aspirational customer is willing to pay and the cost of retailing in Tier 2+3 cities of India is where Cantabil is focused.

"Awareness is increasing due to social media. The spread between lower costs in rentals and aspirational pricing-driven purchases by the Tier-3 consumer is a perfect market segment for us, and we want to focus on serving it."

"Tier 1 is just 10%. It helps us build a brand by being aspirational as we are located in some of these premium places—but they aren’t our core drivers."

Then, there are other factors at play, too. In addition to the rental costs, temperature, seasons, and festivals also influence Cantabil’s growth.

"We haven't entered South India yet because the profit in winter wear is not there in summer areas. Winter products have good margins in the North. We are opening 70-80 stores annually. In the next 2-3 years, we will think about South India."

"In Tier 1, like Delhi, we started from Delhi NCR. My showrooms have opened in every market. Bombay is very expensive—shops are small and rent is very high. So selection is difficult, and there's no sale of winter wear. In Bombay, you have to be very choosy and careful."

"When I opened the first store in Karol Bagh in Delhi (non-Cantabil), I gave rent of ₹2 lakh per month. This was in 1998 for 1,200 square feet. Today I am giving ₹25 lakh for the same store. The square footage has increased a little to 2,100 square feet, but the cost per squre foot has become 10x."

"In contrast, the rental market in Kolkata is very cheap. The seasonal Durga Pooja market is big. There, 70% sales come during Durga Pooja. Everyone buys there during that period."

Then there is the question of competitive forces directly affecting a company’s profit pools.

"New competitors play a different game—mostly in fast fashion model. They go to different types of customers than us. In big malls, their format is also big. The average size of stores we opened this year is 1,700 square feet. Their store size is 4,000-5,000 square feet."

"Our focus is less on fast fashion, more on formal and basic garments that any age group can wear. Today, you can wear my clothes, and your father can wear them. We work more in formals and basics, less in fashion."

The product mix is well-balanced across categories:

"20% I sell suits, blazers, and formal trousers—approximately worth ₹140+ crores. Casual and formal shirts together: 27%. Denim and casual pants: 18-20%. Knitwear (T-shirts, sweatshirts, woolens, hoodies, jackets): 22-23%. Ladies wear: 10%. Kids: 3-4%. Accessories: 5%."

"I have 50 exclusive stores for ladies’ wear. I have to work hard on that model too. If my model becomes more profitable, there is margin but less than Cantabil men's. So I have to bring it to an equal level. With the same speed, I can open 400-500 ladies exclusive stores if there is the same margin."

"We started focusing on brand building in 2017. We focused on visual appeal, advertising, showroom furniture—world-class furniture, and product improvement. If you go to a store and compare it with any international brand, you won't see any difference. Product quality, showroom ambiance—world class."

Category Extensions enabling Horizontal Integration

The retail model and the product channel fit that Cantabil has there enables the company to conduct rapid product experimentation and real-time market feedback.

"Since we operate our own customer-facing stores, we’re uniquely positioned to test new product lines swiftly," Vijay explains.

"If a product doesn’t resonate with consumers, we withdraw it immediately. If it performs well, we quickly scale production and expand its availability across locations. This agility keeps us closely aligned with evolving consumer preferences."

This dynamic feedback loop has paved the way for Cantabil’s foray into new product categories.

"In 2010, we introduced a range of accessories and innerwear segments, which received a strong initial response. Perfumes were introduced in 2021."

"We’ve also ventured into the range of footwear in the year 2024—including casual shoes, sports shoes, walking shoes, and sneakers—all under the Cantabil brand," he notes.

Cantabil continues expanding into new categories.

"This year, we went live with formal shoes, sports shoes, walking shoes, sneakers, all under the Cantabil brand. Now we have started with undergarments. They are getting a good response. Then we will have perfumes."

Category-wise Revenue Split

Men's Wear: 81%

Women's Wear: 11%

Accessories: 5%

Kids Wear: 3%

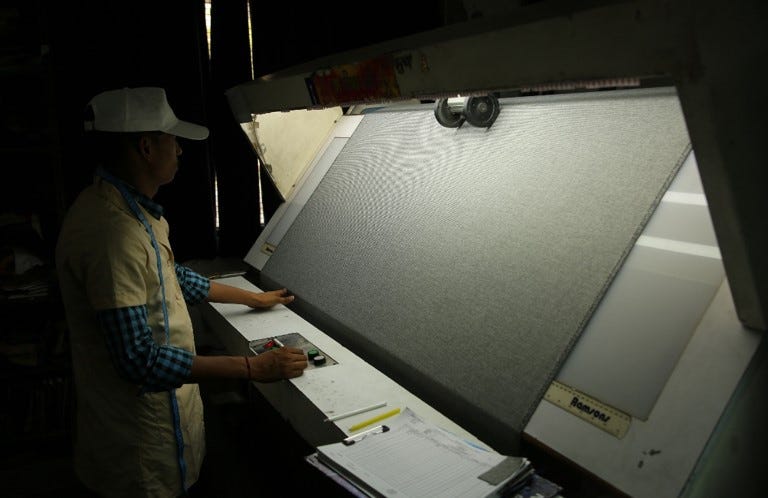

Manufacturing Excellence

Cantabil’s in-house manufacturing infrastructure is a great example of Cantabil’s focus on vertical integration—ensuring quality, operational control, and long-term value creation.

Located on a 3-acre industrial site, the state-of-the-art facility spans over 200,000 square feet and employs more than 1,700 skilled manpower. Outfitted with advanced German and Italian machinery—particularly for suit manufacturing—the plant meets global standards of craftsmanship.

“There are only a handful of facilities in India—perhaps five or six—that can produce suits at this level of precision and finish,” notes Vijay.

What makes this more remarkable is the capital efficiency behind it. The entire facility was developed with a modest ₹5–6 crore loan, fully repaid through internal accruals—underscoring the company’s disciplined financial management.

Vijay notes the potential to grow:

"Right now we're making 1.5 lakh garments per month. Our production is 25% of our total market requirements. The rest are sourced from fabricators and vendors—75% is purchased from dedicated units and direct vendors."

Hiring, Delegation, and Focus

Vijay’s approach to talent acquisition departs from conventional playbooks. Rooted in experience and emotional intelligence, his hiring process is deeply intuitive.

"When I interview a candidate, it usually takes just 15 to 20 minutes to understand their essence," he explains.

"I observe their tone, speech pattern, body language, and the authenticity in their words. If I sense a genuine, grounded energy—a positive instinct—I proceed with confidence. On the other hand, when someone seems to speak without depth or conviction, that becomes evident very quickly. Years of engaging with people have sharpened that instinct, and in over 95% of cases, my judgment has held true."

While credentials and experience are acknowledged, they are not the deciding factors in his assessments.

"I certainly do a keen review of a person's background and résumé, but what matters more is their communication style, their ability to present ideas clearly, persuade constructively, and carry themselves with composure and respect."

For Vijay, leadership potential is substantially measured by academic degrees, but defined by interpersonal intelligence & leadership.

"An individual’s career progression is ultimately driven by their working style, their ability to align with a team, and how effectively they engage with colleagues—both subordinates and superiors. These are the attributes that build strong organizations."

The Support System

At every critical juncture of his entrepreneurial journey, Vijay credits his family as an unwavering pillar of strength.

"My wife has been a constant source of encouragement,” he shares. “Her belief in me never wavered. She always urged me to give my best to building Cantabil, even in the most testing times."

In 2006, Vijay’s son, Deepak, entered the business at the age of 20, taking charge of front-end operations.

"From day one, Deepak demonstrated clarity, initiative, and a sharp understanding of customer-facing dynamics," Vijay recalls.

"Over time, he evolved into a capable leader, growing alongside the company and playing an integral role in shaping its future."

Measured Ambition

Vijay's vision for the future is ambitious yet grounded.

"I think my growth is in the next 7-8 years. I want to reach ₹2,500 crores in sales."

"₹2,500 crores means 3.5 times the current size. This is a very manageable goal. 3.5 times means we will have to increase stores from 600 to almost 2,000-2,500 stores."

Reflecting on his journey, Vijay offers practical advice for young entrepreneurs.

"Once your education is complete, whatever opportunity lies ahead—whether it’s a family business or a job—embrace it fully. Don’t wait for the ‘perfect’ beginning. If you apply yourself sincerely, you can shape that opportunity into something far greater. Ultimately, it is your thinking and vision that determine the direction your journey takes."

His core principles are simple but powerful.

"The most important things are honesty, hard work, and transparency. The more clearly you speak—to the point, without double-talk—and the harder you work with focus, the more successful you'll be."

He warns against the modern obsession with rapid scaling.

"The biggest problem is that people want to grow too fast. We should remember there's no shortcut. You have to keep working in the right direction consistently. If you keep working in the right direction, you will grow."

Vijay shares an interesting insight for manufacturing luck.

"Look, luck works, but you have to work first. Luck will work later. If you put in effort and don’t stop putting in effort despite not getting any growth immediately, you will eventually grow. I believe that luck can be manufactured. People make their own destiny. Luck doesn't work alone. It works when you put effort."

Final Reflections

Today, at 65, Vijay Bansal represents a unique breed of entrepreneur.

"My father worked till 84 years. He went to his shop on the last day. So I have a vision of 10-15 years. There is a lot of scope in everything. There is no limit to anything."

The company he has built stands as a testament to fundamental business principles executed with discipline and persistence.

Looking back at the complete journey—from a small general store in Jind to a ₹721 crore revenue business—Vijay's story proves that in business, as in life, there are no shortcuts to lasting success. Only hard work, honesty, smart execution, and the courage to persist when everyone else thinks you should quit.

"In my life, whatever work I do, I do it with complete transparency and hard work. Be far-sighted and stick to your decisions," he concludes, the wisdom of four decades in business condensed into a simple truth.

Safe Harbor Statement: This story may contain forward-looking statements that involve risks and uncertainties. Actual results may differ materially from those projected.This story is based on extensive interviews with Mr Vijay Bansal, Founder, Chairperson, and Managing Director of Cantabil Retail India Limited (NSE: CANTABIL), a publicly listed company with over 600 retail stores across India and annual revenues of ₹720+ crores (FY25).

This interview was originally conducted in March 2025 in Hindi and has been translated for our reader-investors.

For providing feedback, please write to us at banjan@tal64.com